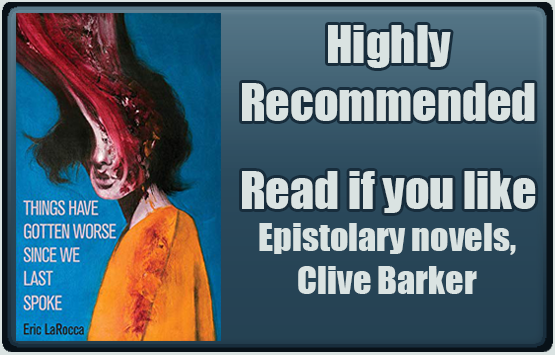

Formats: Print, audio, digital

Publisher: Weirdpunk Books

Genre: Body Horror, Psychological Horror, Romance

Audience: Adult/Mature

Diversity: Gay author, lesbian main characters

Content Warnings (Highlight to view): Animal Death, Death, Mental Illness, Gaslighting, Homophobia, Suicide, Verbal/Emotional Abuse

Blurb

Sadomasochism. Obsession. Death.

A whirlpool of darkness churns at the heart of a macabre ballet between two lonely young women in an internet chat room in the early 2000s—a darkness that threatens to forever transform them once they finally succumb to their most horrific desires.

What have you done today to deserve your eyes?

Holy shit…this book. Definitely shouldn’t have read it at 1 am.

This epistolary novella starts out innocently enough. It’s the early 2000s and a young woman named Agnes is selling her antique apple peeler on a LGBTQ+ message board. Another young woman, Zoe, offers to buy the apple peeler. The two email back and forth and start up a friendship. Agnes is having a really tough time and Zoe does something incredibly kind and generous to help her out. Awwww. It also turns out both women are gay and developing feelings for each other. Sounds like a sappy Hallmark Christmas movie doesn’t it (if Hallmark ever aired anything that wasn’t incredibly heteronormative)? Except then things start getting kind of weird (so more like a Lifetime Christmas movie). Agnes, who’s life honestly kind of sucks, is beholden of her “guardian angel” and a little too willing to please her. Zoe wants to push Agnes out of her comfort zone and asks her “What have you done today to deserve your eyes?” Super creepy, although nothing necessarily sinister yet. Still, relationship red flags are starting to pop up. As the two grow ever closer, Zoe suggests they enter a BDSM/sugar mama relationship which Agnes immediately agrees to. Zoe will email tasks which Agnes must complete to please her “sponsor” (Kudos to LaRocca for using sponsor/drudge instead of master/slave which can have racist connotations). Things start going downhill rapidly as both women prove how emotionally unstable they really are.

Twitter User @daveaddey noticed something interesting about Hallmark Christmas movie posters. Namely that they all look like they’ll eat your soul.

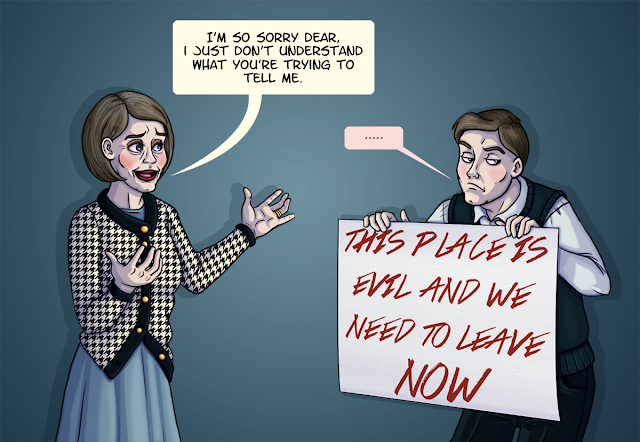

BDSM is not inherently harmful. Even when it’s meant to cause pain and discomfort, it shouldn’t result in any permanent physical, emotional, or mental harm; every act should be consensual, not coerced and when I say consensual, I mean enthusiastic consent, not the lack of a “no” or safeword. But like with all things, there are people who take it too far. Doms are supposed to prioritize the safety and well-being of their submissive, but Zoe is more interested in seeing how far she can push her new toy before it breaks. She doesn’t listen when Agnes tells her she’s uncomfortable and ignores the fact that a desperately lonely Agnes in not in the right headspace to make informed decisions. Zoe even makes her perform acts that threaten Agnes’ ability to function in everyday life and takes control of her finances (which is a big red flag). That’s when things start to get really disturbing. Yes, it gets even worse. I won’t reveal any spoilers, suffice it to say this book is not for the squeamish or anyone triggered by depictions of psychologically abusive relationships.

Aftercare is important.

Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke is one of the most uncomfortable and disturbing books I’ve read all year. I spent the final third of the novella squirming and distressed, muttering “Oh no, oh no, oh no” to myself. Watching an abusive relationship develop as a lonely young woman’s mental health declines is incredibly upsetting. The warning signs in the relationship are subtle and easily missed if you don’t know what to look for, at least until it’s too late. And the body horror pairs perfectly with the psychological horror, making the story even more unsettling. This novella may only take an hour to read, but the dread will stay with you for days. So, what have you done today to deserve your eyes?