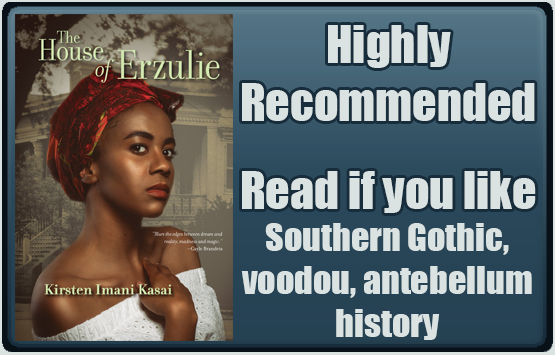

Formats: Print, audio, digital

Publisher: Shade Mountain Press

Genre: Gothic, Historic Horror, Myth and Folklore

Audience: Adult/Mature

Diversity: Black/biracial main characters and author, mentally ill main characters

Takes Place in: Philadelphia and New Orleans, USA

Content Warnings (Highlight to view): Alcohol Abuse, Animal Death, Body Shaming, Child Abuse, Child Death, Death, Drug Use/Abuse, Forced Captivity, Gaslighting, Illness, Kidnapping, Medical Torture/Abuse, Medical Procedures, Miscarriage, Mental Illness, Oppression, Pedophilia, Physical Abuse, Racism, Rape/Sexual Assault, Self-Harm, Sexism, Sexual Abuse, Slurs, Slut-Shaming, Torture, Verbal/Emotional Abuse, Violence, Xenophobia

Blurb

The House of Erzulie tells the eerily intertwined stories of an ill-fated young couple in the 1850s and the troubled historian who discovers their writings in the present day. Emilie St. Ange, the daughter of a Creole slaveowning family in Louisiana, rebels against her parents’ values by embracing spiritualism, women’s rights, and the abolition of slavery. Isidore, her biracial, French-born husband, is an educated man who is horrified by the brutalities of plantation life and becomes unhinged by an obsessive affair with a notorious New Orleans voodou practitioner. Emilie’s and Isidore’s letters and journals are interspersed with sections narrated by Lydia Mueller, an architectural historian whose fragile mental health further deteriorates as she reads. Imbued with a sense of the uncanny and the surreal, The House of Erzulie also alludes to the very real horrors of slavery, and makes a significant contribution to the literature of the U.S. South, particularly the tradition of the African-American Gothic novel.

I received this product for free in return for providing an honest and unbiased review. I received no other compensation. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.

The House of Erzulie is an exquisitely written, thought-provoking work of Southern Gothic fiction that explores themes of identity, love, obsession, and oppression while blurring the line between reality and the supernatural. Kasai’s book also forced me to acknowledge and confront my own complicated feelings and insecurities about my identity as a light-skinned, biracial Black person and reflect on the colorism within the Black community.

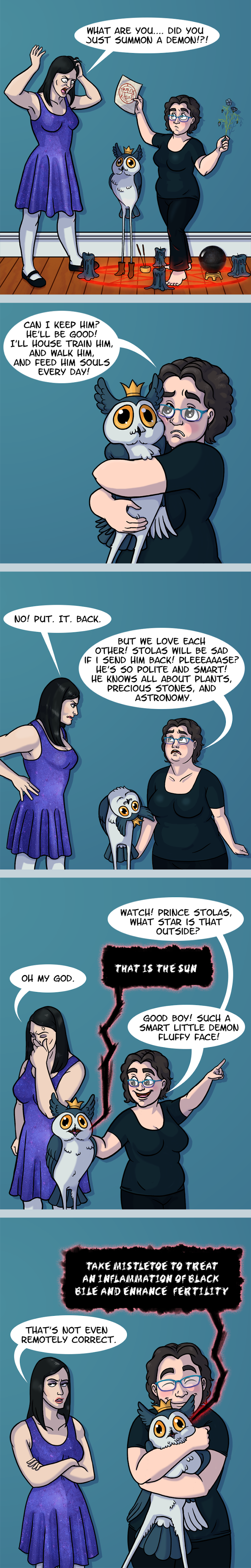

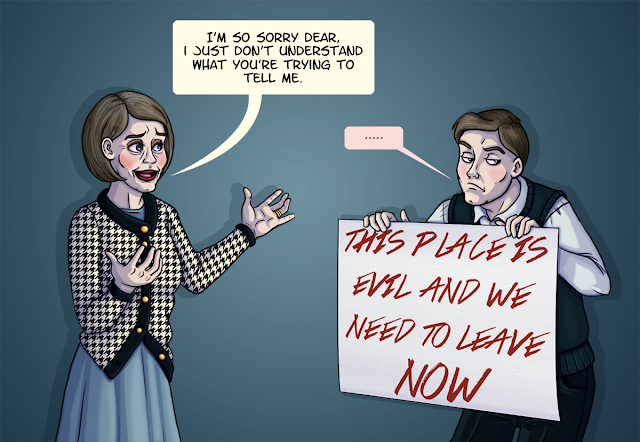

Lydia is a professor of history trapped in a bad marriage with her former advisor Lance, a selfish, serial philanderer who prefers his women young, docile, and naive. Their teenage son is emotionally distant and rarely home. Struggling with depression and a desire to self-harm, Lydia tries to cope with her emotional pain and feelings of isolation by throwing herself into her job, the one area of her life that isn’t falling apart. Ironically, it’s her work, the last vestige of stability in Lydia’s life, that finally destroys her fragile mental health.

At first Lydia thinks nothing of the journals she receives in a packet of historical documents belonging to the once grand Bilodeau plantation in New Orleans. After all, she’s been hired to aid in the restoration of the dilapidated building, even if she finds the monument to slavery distasteful. It’s only on a whim that she chooses to peruse the diaries of Emilie Bilodeau, the progressive daughter of a slave-owning family, and her husband Isidore Saint-Ange, a free-born biracial Frenchman. But as she learns more about the tragic couple’s lives Lydia finds herself strongly empathizing with Emilie’s loneliness and crumbling marriage. But it is Isidore’s journal that finally pushes her over the edge. Once logical and purely scientific in his approach to the world, Isidore becomes increasingly paranoid as a series of poor decisions and bad luck destroy his life. Eventually succumbing to madness, Isidore is imprisoned in an insane asylum convinced he is the victim of supernatural forces. As her own life turns to chaos, Lydia finds herself mirroring Isidore’s destructive actions.

The House of Erzulie has all the elements of a first-rate Gothic story; a distressed heroine kept trapped and powerless. A passionate but ultimately doomed romance. Hints of the supernatural in the form of spirits, curses, and prophetic nightmares that may or may not be products of the antihero’s imagination. A once great home falling into ruin as disease, death, and madness ravage its inhabitants, all set against the backdrop of one of America’s greatest atrocities. Kasai is careful to emphasize how appalling and inhumane the practice of chattel slavery is without using a historical tragedy for cheap scares or trauma porn. Instead Isidore’s rapidly declining mental state reflected in the plantation’s decay and the multiple misfortunes befalling the Bilodeaus is what makes the novel so frightening. I must admit I found it incredibly satisfying to watch such unsympathetic characters suffer karmic retribution (Emilie being the exception) the more gruesome and agonizing the better though I’m sure not all readers will share my taste for schadenfreude. Kasai’s writing is superb, her carefully crafted prose flows like poetry and evoked strong emotions in me. I’ll share one of my favorite passages here:

They say “love is not a cup of sugar that gets used up” but it is. Spoonful by spoonful, grain by grain, the greedy, the needy, and the hungry consume it and demand more until the bowl is empty. Then they run away, jonesing for a fix from another source. Each betrayal, every insult or injury depletes the loving cup and leaves the holder bitter. It’s a bitterness I can taste, and it sits on my tongue like the foulest medicine.

Kasai also did extensive research for her novel, as is obvious from the story’s numerous references to historical events and the accuracy with which mid-19th century healthcare is depicted. The Spiritualist movement (which Kasai notes provided one of the few public platforms for women at the time), the yellow fever epidemic of 1853, and the anti-Spanish riots of 1851 all make appearances in The House of Erzulie. But it’s the lives of her gens de couleur libres, or “free people of color” characters that deserve special attention. While I was initially disappointed by how little attention the narrative paid to the stories and voices of the slaves, it was a nice change of pace to read a novel that focused on the lives of free Black characters. Despite the significant role they played in US history, wealthy, free Blacks in the antebellum South rarely make an appearance in historical fiction.

The majority of the novel is set in Louisiana, once home to the largest population of gens de couleur libres in the US. Forming an intermediate class below White colonizers but above slaves, free Blacks achieved more rights, wealth, and education in the French settlement than in any of the British colonies. Professor Amy R. Sumpter notes in her article Segregation of the Free People of Color and the Construction of Race in Antebellum New Orleans that before the state currently called Louisiana was stolen “acquired” by the US in 1803 “the cultural blending of French, Spanish, and African traditions… created an atmosphere of racial openness in Louisiana and particularly New Orleans that stood apart from much of the rest of the South. Aspects of the unique racial atmosphere included a tripartite racial structure and racial fluidity.” Much of this was due to the Code Noir, an edict originally issued by King Louis XIV in 1724 that defined the legal status of both slaves and free blacks and imposed regulations on slave ownership. While no less cruel and inhumane than any of the other laws governing the enslavement of human beings, the code did make allowances not found in the rest of country.

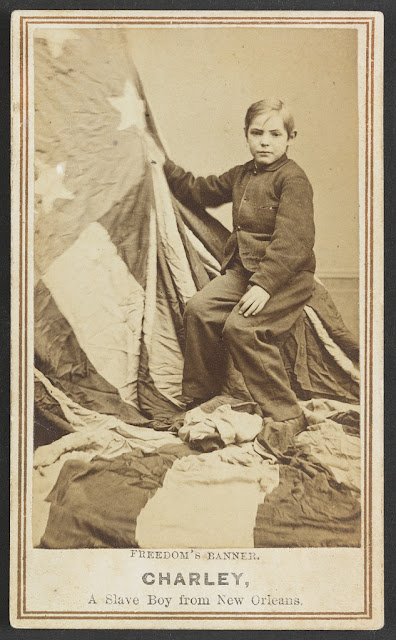

The US followed a strict “one drop” rule that classified anyone with Black ancestry as Black. Mixed raced individuals were given offensive labels depending on their percentage of “Black blood”. “Mulattos” were biracial with one Black parent and one White. “Quadroons” were a quarter Black, “octoroons”(also called “mustees”) one-eighth, and “quintroons” (or “mustefinos”) one-sixteenth. In her acclaimed essay Whiteness as Property civil rights professor Cheryl Harris explains that this complicated system was “designed to accomplish what mere observation could not: That even Blacks who did not look Black were kept in their place.” English colonies also practiced partus sequitur ventrem (Latin for “the offspring follows the womb”) a law that gave a child the same legal status as their mother. So a mixed-race child born to an enslaved mother would be born into slavery, while the child of a free woman would also be free.

Charley Taylor was the “quadroon” son of White slave-owner Alexander Scott Withers and a biracial slave named Lucy Taylor. Because his mother was a slave Charley was also born into slavery and sold by his father to a New Orleans plantation. Abolitionists often used images of White-passing slaves to elicit sympathy as White audiences were more likely to be identify with the suffering of people who looked like them.

Most of the main characters in The House of Eruzile are upper class gens de couleur libres all of whom approach their Blackness and privilege differently. Emilie’s father, Monsieur Bilodeau, is a willing and enthusiastic participant in the slave economy and chooses to idolize Whiteness, despite having a Black grandmother. It’s a sad fact that some free Blacks became slave owners themselves, and many of them lived in Louisiana. While I can’t pretend to know the motivations of long-dead men, Kasai makes it clear that M. Bilodeau does it because he’s greedy, racist scum, a twisted amalgamation of Uncle Tom and Simon Legree. Isidore is shocked and disgusted by the treatment of the slaves on his in-laws plantation (slavery would’ve just been abolished in France), but is unwilling to risk his own privilege and wealth by objecting or leaving. Well-educated and used to a comfortable existence Isidore married into the Bilodeau family so he could continue enjoying a life of leisure rather than be forced to get a job. He does his best to ignore the suffering of the plantation’s slaves, as if this will somehow absolve him of his participation in a racist and inhumane system. Emilie, on the other hand, uses what little power she has to advocate for her family’s slaves, including her great-great-aunt Clothilde (yup, her dad wouldn’t even free his own family-members) and becomes involved in the abolitionist movement. She does her best to try to convince her husband to move North and free the Bilodeau slaves once they inherit the plantation but is always shot down. Finally, there’s P’tite Marie, the light-skinned daughter of Marie Laveau, a free-woman with significant influence.

While Kasai is undoubtedly a talented writer, I was troubled by the way she portrayed P’tite Marie as a one-dimensional Jezebel who uses voodoo to literally enchant her lovers. Her characterization is in sharp contrast to Emilie’s role as the virtuous mother, bringing to mind the deeply problematic Madonna/whore dichotomy. P’tite Marie would certainly have been exploited by men who fetishized free Black women, as is evident from the stories of Quadroon Balls, plaçages and “fancy maids,” so implying that she is sort of succubus who takes advantage of men didn’t sit right with me. Admittedly, we only get to view P’tite Marie through the lens of an unreliable, misogynist narrator who is seemingly incapable of accepting responsibility for his own actions and who is quick to blame her for his philandering. Still, it would’ve been nice to learn more about P’tite Marie as a person rather than a sexual fantasy. Personally, I would have much preferred if P’tite Marie and Emilie had realized that all the men in their lives were awful and decide to run away together.

The house in the background is based on the Oak Alley Plantation in New Orleans. Now a museum, Oak Alley boasts tours of the facility, a beautiful venue for weddings and reunions, a well-reviewed restaurant, and overnight cottages. What could be more relaxing than sipping mint juleps at the site of significant human right’s abuses and suffering? Maybe Auschwitz should start doing weddings.

Emilie was another character I took issue with. I found her naivety grating rather than endearing, and it concerned me that the Whitest character in the book was written to be the most sympathetic. To Kasai’s credit she does a wonderful job creating a mixed-race Gothic heroine without making her a tragic mulatta. Emilie is still a tragic character, but none of that is related to her identity. She is not ashamed of being mixed and is astutely aware of her good fortune. She uses her privilege to help others and would gladly give up her wealth if it meant freedom for the Bilodeau’s slaves. Instead of lamenting the “single drop of midnight in her veins” Emilie’s greatest source of ignominy is her family’s arrogance and lack of empathy. As she matures, she begins pushing back more aggressively against the injustices she perceives. And yet, I still deeply disliked her. But more on that in a moment.

Emilie was not the only character that inspired a strong reaction from me. Lydia, like many mixed race folks, has a complicated relationship with the White grandparents who raised her, and her family problems resonated deeply with me. I don’t even know most of my White family, nor do I want to, as they’re racists who disowned my mother for marrying my Black father. My mother is amazing and dedicated to anti-racism work, but I feel nothing but contempt for the biological family that labeled me a “jigaboo baby.” Meanwhile Isidore and M. Bilodeau reminded me of the worse aspects of the mixed community; those who choose inaction, thereby becoming complicit in the system of White supremacy, and the self-hating Blacks who reject their race and actively promote racism and colorism to get ahead. I could easily imagine the reprehensible M. Bilodeau in a blue vein society wearing a “Make America Great Again” hat while defending voter suppression and laughing at racist jokes. Emilie’s father is clearly an irredeemable villain who has no qualms about abusing his slaves, while Isidore is given more complexity and a conscience. Unfortunately, his guilt has no effect on his actions, and I was hard-pressed to dredge up even a shred of sympathy for Isidore and his hypocrisy. This is a perfect example of why intent doesn’t matter. While Isidore may not be an unrepentant racist like his father-in-law both men selfishly used their privilege for their own benefit at the expense of other Black people. It’s hard to say if his inaction makes him more or less morally reprehensible that his monstrous father-in-law.

I suspect that the reason I felt so much animosity towards Emilie, even though Isidore and M. Bilodeau are much more reprehensible, may stem from my own experience and insecurities as a White-passing Black person. I struggle daily with the guilt and resentment I feel knowing that while I’m undoubtedly oppressed by a White supremacist system, it also gives me an unearned advantage over others. I, and others like me, enjoy higher wages and are perceived as more intelligent while those with darker skin are given longer prison sentences, are three times more likely to be suspended from school and struggle to find partners. My grandfather could join Black fraternities that implemented paper bag tests, and probably used his light complexion to secure jobs as a physician. His grandparents were house slaves (and the children of their owner) like the ones described by James Stirling in The Life of Plantation Field Hands and Malcom X in his Message to Grassroots speech. Not only am I treated better by Whites (who were responsible for this racist caste system in the first place) but even the black community puts a high-value on my pale skin. Colorism is so deeply ingrained in society that skin-whitening creams are a $20 billion industry. My Black grandmother used to keep my father and his sister out of the sun so they wouldn’t be “too dark.” There’s a #Teamlightskin hashtag on Twitter. A color-struck, light-skinned manager at Applebee’s called his darker skinned employee racist slurs and suggested he bleach his skin. My passing privilege (most people assume I’m Jewish, Italian or Latinx until I correct them) and proximity to Whiteness means I can easily avoid the racist aggression the rest of my family experiences on a daily basis.

This a fake graph, but it’s based on actual data.

Because Emilie is so White, I instinctively questioned whether she could even be considered Black, just as my own melanin-deficient skin often makes others question my identity. While I can easily dismiss comments of “you’re not really Black” from Whites who are pissed I told them not to say the n-word (I could be Whiter than Conan O’Brien and you still can’t fucking say it Karen), it’s a lot harder when the remarks come from other Black people who make it clear they don’t want me in their spaces. But as much as I’m tempted to self-indulgently sulk, I can’t ignore the very valid concerns of darker skinned Black folk who are frequently pushed aside in favor of people like me. Yes, I, and other light-skinned BIPOC may deal with frequent microaggressions and sometimes even outright hostility, but we’re still much more welcomed by a racist society then we would be if our skin were darker. Given all this it’s no wonder my intrusion on BIPOC spaces is often called into question. Yes, I have racial trauma, but is it right for me to complain to those who are clearly dealing with so much more? It would be like crying about having my purse stolen to someone whose had their home burnt down and lost everything. Denying that I have privilege is incredibly harmful to the Black community as are comments like “we’re all Black, why are we dividing ourselves even more?” Tonya Pennington does an excellent job encapsulating my feelings on the matter in their article for The Black Youth Project:

…despite my empathy for [Ayesha Curry], I disagree with her conclusion for why she isn’t accepted by the Black community. Both of us are light-skinned, and we know light-skinned Black people are often considered more desirable than dark skin Black women because of colorism. As much as she may have been picked on for being “different,” like me, it’s inevitable that she also experienced a host of privileges both within and outside the Black community for the same thing.

To be clear, in my personal experience most other Black people have been extremely welcoming to me and are sympathetic to the unique challenges of being mixed race. I am eternally grateful to everyone who has shown me such support and compassion, even when dealing with their own problems. They didn’t need to, and it was incredibly kind. I try my best to avoid demanding pity, taking over conversations, or otherwise making things about me when I’m in Black spaces. To do otherwise would be reprehensible. I know I have it a lot easier that others, and it’s my responsibility to use my light-skinned privilege to combat systemic racism when I can.

As Afropunk writer Erin White explains “Light skin people have a responsibility to call out colorism and be honest about the privileges they benefit from.” Blogger Amanda Bonam, founder of The Black & Project even gives examples on how she confronts her own light-skinned privilege. Unfortunately, the best ways to oppose colorism isn’t always obvious, and even good intentions can be harmful if one isn’t cautious. Like all allies we walk a fine line, confronting colorism without speaking over those without light-skinned privilege. For instance, as a person with light-skinned privilege, I constantly worry that I’m either not doing enough, or else I’m so vocal that I’m silencing other Black voices. Like my “white-passing” guilt, I push these worries down because, again, it’s not about me and those emotions are unhelpful. But they still exist no matter how much I try to deny them, because that’s how feelings work. Which brings me back to Emilie, because in her I saw my own insecurities.

Mentally I condemned Emilie for what I saw as meager attempts to help the Bilodeau’s slaves, despite benefiting so much from colorism. When Emilie bemoaned the fact she couldn’t do more, I bristled at how she seemed to be selfishly focused on her own suffering. I cast her in the role of White savior whose negligible struggles and accomplishments were lauded above those of the Black characters. Except Emile isn’t White, at least she wouldn’t have been in 1850. Hypodescent rules would have meant she’d be labelled Black by society, and there was certainly no benefit to having a Black great-grandparent in antebellum Louisiana. And how much could she have possibly done to help the slaves? Emilie was a woman, with no power and her resources were completely controlled by the men in her life. When she spoke out she was ignored. She couldn’t purchase anyone’s freedom as Isidore had complete control of her finances. The laws were not on her side. Much of the novel’s focus is on Emilie’s feelings, but it’s also written as a diary, where she would have recorded her personal thoughts, struggles, and misgivings. There’s no indication she was putting her feelings over those of the slaves; to the contrary Emilie seems to hide her guilt and frustration from everyone save her White abolitionist friend.

So did I judge Emilie, Kasai’s heroine, unfairly because I projected so much of myself onto her? Or was I right to be critical of a light-skinned character who once again is given the spotlight over dark-skinned Black folk? As of now, that’s not an answer I can provide. Instead I encourage the reader to draw their own conclusions about Emilie. All I know is that any book that can provoke so much both emotionally and intellectually is well worth a read.