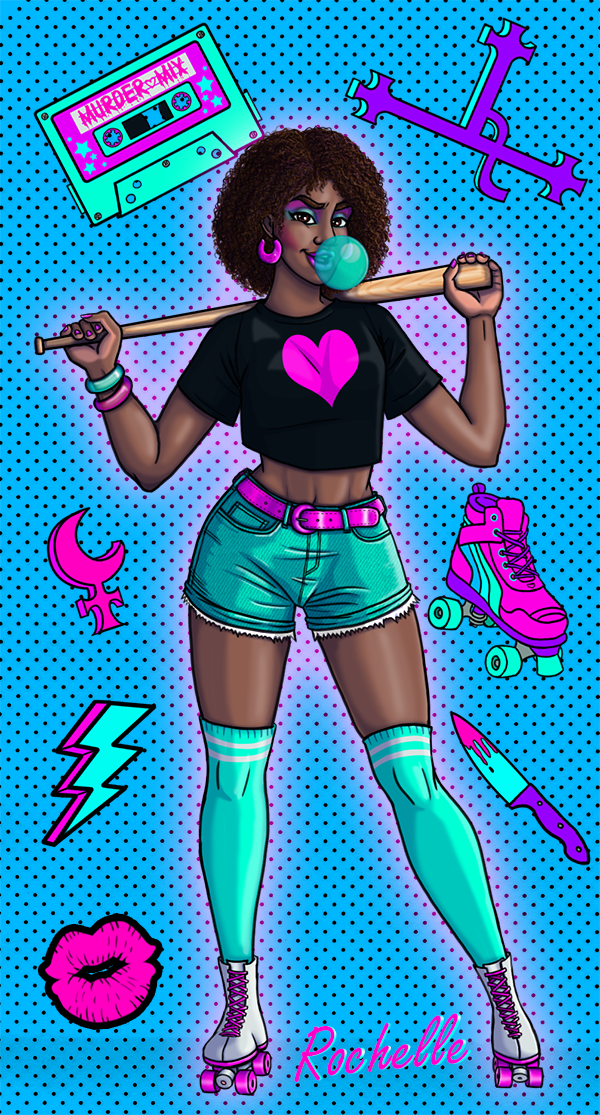

Formats: Print, audio, digital

Publisher: Dancing Cat Books

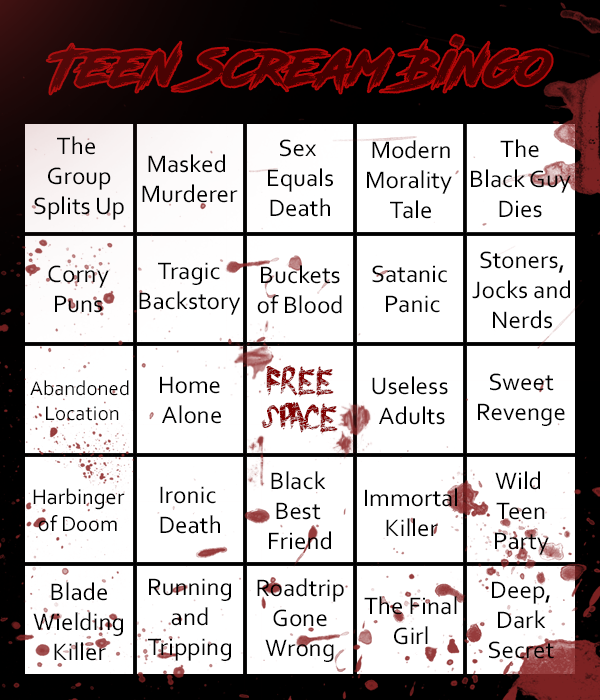

Genre: Apocalypse/Disaster, Body Horror, Sci-Fi Horror

Audience: Y/A

Diversity: American/Indian and Indigenous characters (Mostly Métis, Anishinaabe, and Cree), Black/Indo-Caribbean/Biracial character, gay male characters

Takes Place in: Toronto, Canada

Content Warnings (Highlight to view): Alcohol Abuse, Amputation, Child Abuse, Child Death, Child Endangerment, Death, Drug Use/Abuse, Forced Captivity, Kidnapping, Medical Torture/Abuse, Pedophilia, Police Harassment, Racism, Rape/Sexual Assault, Sexual Abuse, Slurs, Suicide, Violence

Blurb

In a futuristic world ravaged by global warming, people have lost the ability to dream, and the dreamlessness has led to widespread madness. The only people still able to dream are North America’s Indigenous people, and it is their marrow that holds the cure for the rest of the world. But getting the marrow, and dreams, means death for the unwilling donors. Driven to flight, a fifteen-year-old and his companions struggle for survival, attempt to reunite with loved ones and take refuge from the “recruiters” who seek them out to bring them to the marrow-stealing “factories.”

***CONTENT WARNING: In this review I will be discussing Indigenous American (Canadian, Mexican, and the US) history and residential schools/Indian boarding schools, with a primary focus on Canada where the Marrow Thieves takes place. I will be touching on genocide, forced assimilation, abuse, sexual assault, trauma, and addiction. There will also be images of verbal abuse and the effects of trauma. Please proceed with caution and take breaks if you need to. For my Indigenous readers: if you feel at all distressed or disturbed while reading this, or just need support in general, there are resources for the US and Canada here and here respectively. If you need extra help you can also find Indigenous-friendly therapists here and here to talk to. If you are a abuse survivor, are being abused, or know someone who is, please go here. There are further links at the end of the review. Please reach out if you need to!***

I have tried to use mainly Indigenous created articles, websites, books, films, and interviews for reference when writing this review. I have also included multiple quotes from residential school survivors, as I felt I could not do justice to their vastly different experiences without using their own words. However, I can only cover a fraction of a long and complex history. I strongly encourage everyone to check out the books, videos, and podcasts I have listed at the end of the review. Kú’daa Dr. Debbie Reese for providing such an excellent list of suggestions for residential school resources! They were a huge help in this review. And speaking or Dr. Reese, check out her review of The Marrow Thieves as well as Johnnie Jae’s Native book list. And another big thank you to Tiff Morris for being my sensitivity reader for this review. Your help and advice was invaluable! Wela’lin!

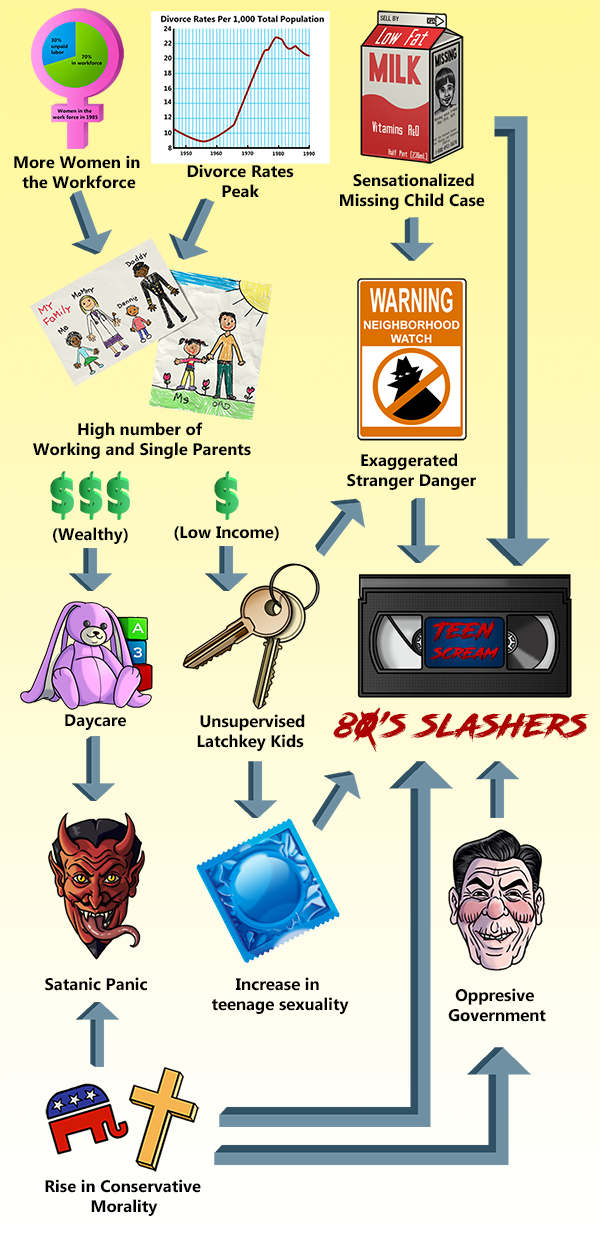

When I first read The Marrow Thieves years ago it didn’t impact me the way it does now. Back in 2017 a worldwide pandemic still existed solely in the realm of science fiction. Much like a giant asteroid destroying the earth, it was technically possible but so unlikely that such a scenario wasn’t worth worrying about. Re-reading the dystopian horror novel in 2020 was a completely different and utterly terrifying experience. Even knowing how the story would end was not enough to quell my anxiety and I felt on edge the entire time. The fact that Cherie Dimaline’s used real world atrocities committed against Indigenous people just makes the story feel even more plausible and horrifying. Water rights, violence against Indigenous women, cultural appropriation, climate change, cultural erasure, and the trauma caused by residential schools are all referenced.

The book opens with the protagonist Frenchie, a young Métis boy, watching helplessly as his Brother Mitch is beaten and kidnapped by Recruiters, a group of government thugs tasked with capturing Indigenous people for the purpose of extracting their bone marrow. Now alone, and with no idea how to survive on his own Frenchie has to be rescued from starvation by a small band of Indigenous (mostly Anishinaabe and Métis) travelers. The group welcomes the young boy as one of their own, and he soon comes to see them as an adoptive family as the ragtag bunch works together to survive and protect each other.

Miig is the patriarch of the group, an older gay gentleman who likes to speak in metaphor and teaches the older kids Indigenous history through storytelling. He also trains Frenchie and the others to hunt, travel undetected, and generally survive in their harsh new reality. Miig might seem cold at first but he genuinely loves the kids, he just prefers to show it through actions rather than words. Dimaline did an excellent job writing Miig and he felt like a real person rather that a lazy gay stereotype. I absolutely adore his character. He’s got the whole “gruff but kind dad” thing going. Minerva is another one of my favorites, a cool and cheerful Elder who acts as the heart of the group and teaches the girls Anishinaabemowin, as most of the kids have lost their original languages. She keeps all of them to the past. Minerva also raised the youngest member of the group, Riri, a curious and spunky 7-year-old who ends up bonding with Frenchie. Riri was only a baby when she was rescued and has no memory of a time before they were forced into a nomadic lifestyle in order to avoid the Recruiters so, unlike the others, she has nothing to miss. Cheerful and lively Riri never fails to raise everyone’s spirits or give them hope for a better future.

The rest of the kids range from nine to young adulthood. Wab is the eldest girl, beautiful and fierce and “as the woman of the group she was in charge of the important things.” Then there’s Chi-boy, a Cree teenager who rarely speaks. The youngest are the twins Tree and Zheegwan, followed by Slopper, a greedy 9-year-old from the east coast who likes to complain and brings his adoptive family the levity they all need. Later on they’re joined by Rose, a biracial Black/White River First Nation teen who Frenchie immediately develops a crush on. And I can’t really blame him because Rose is a total bad ass. All of them have lost people to the residential schools and some, like the twins, were even victims of “marrow thieves” themselves. But they all support each other and survive despite the difficulties they’ve faced.

No one knows what caused the dreamless disease rapidly infecting the country, an illness that causes the victim to stop dreaming and slowly descend into madness, only that Indigenous people are immune. And yes, I do appreciate the irony of a plague that only affects Colonizers. Perhaps it’s divine retribution for Jeffery Amherst’s (yes that Amherst) germ warfare. When their immunity is discovered people begin to flock to Native nations begging for help. But Indigenous people are understandably reluctant, having been burned too many times before. They don’t want to share their sacred ceremonies and traditions with outsiders, and for very good reason. Non-Natives quickly get tired of asking and do what they do best: take what they want, in this case Indigenous practices and later Indigenous bodies. The few survivors who do manage to escape the new residential schools often return with parts of themselves missing, an apt metaphor for real residential schools. Although set in a fictional future The Marrow Thieves dives into a past that Colonialism has actively tried to suppress.

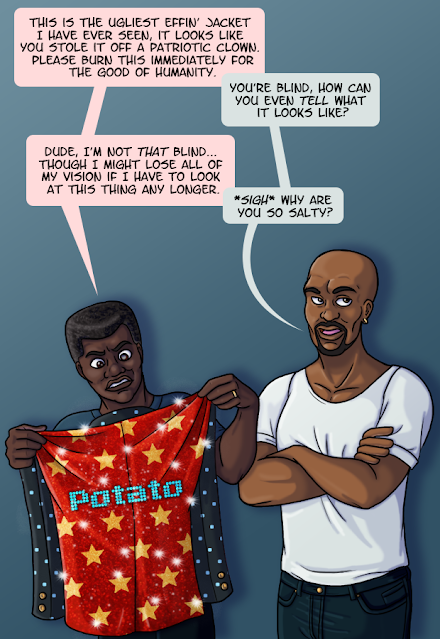

Indigenous history is rarely taught in either US or Canadian schools (outside of elective courses) and what is taught is often grossly inaccurate. To quote Dr. Debbie Reese’s post about representation in the best-selling paperbacks of all time: “23,999,617 readers (children, presumably) have read about savage, primitive, heroic, stealthy, lazy, tragic, chiefs, braves, squaws, and papooses.” In America we’re taught that the Wampanoag (who are never mentioned by name) showed up to save their pilgrims friends from starvation and celebrate the first Thanksgiving, with no mention of the English massacre of the Pequot, Natives being sold into slavery, or the Colonists’ grave robbing. After 1621, mentions of American Indians are scarce to non-existent. There might be a brief paragraph here and there in a high school textbook about the Iroquois Nation siding with the British in the Revolutionary War, or the Trail of Tears.

A 2015 study of US history classes, grades K-12, showed that over 86% of schools didn’t teach modern (post-1900) Indigenous history and American Indians were largely portrayed “as barriers to America progress. As a result, students might think that Indigenous People are gone for one reason—they were against the creation of the United States.” Few students are ever told about the mass genocide of American Indians, smallpox blankets, the government’s unlawful seizure of Native land, the many broken treaties, destruction of culture, and forced experimentation. American Indian writer and activist Suzan Shown Harjo points out in an interview “When you move a people from one place to another, when you displace people, when you wrench people from their homelands, wasn’t that genocide? We don’t make the case that there was genocide. We know there was, yet here we are.” You would think that American history would dedicate more than a paragraph to THE PEOPLE WHO FUCKING LIVED IN AMERICA. I’m not that familiar with the Canadian education system, but according to Métis writer and legal scholar Chelsea Vowel they’re not much better at teaching the history of First Nation, Inuit, and Métis people. The omission of Indigenous Americans and Canadians from history lessons is just another form of erasure that contributes to the continued systemic oppression of First Peoples by a racist and colonialist system.

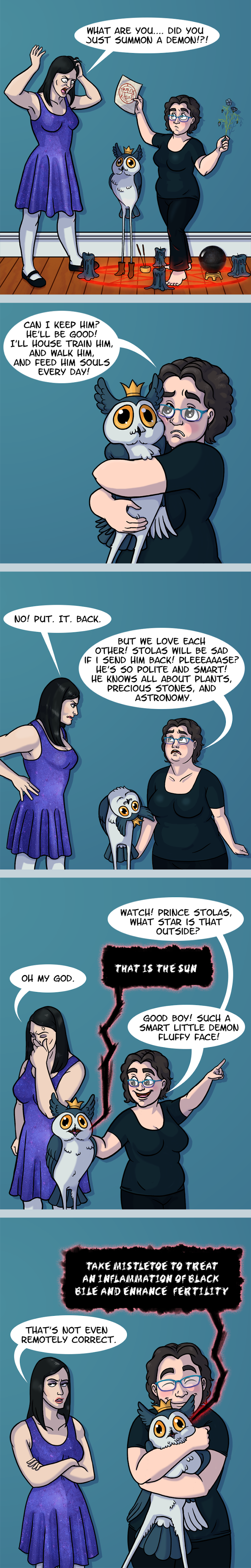

The sad thing is, the “Pilgrim and Indian” drawings are based on actual, present day “lessons” from teaching websites. This comic is loosely based on my experience as the only Black kid in class when we learned about the Civil War. The Seneca girl is wearing a “Every Child Matters” orange shirt for Residential Schools survivors.

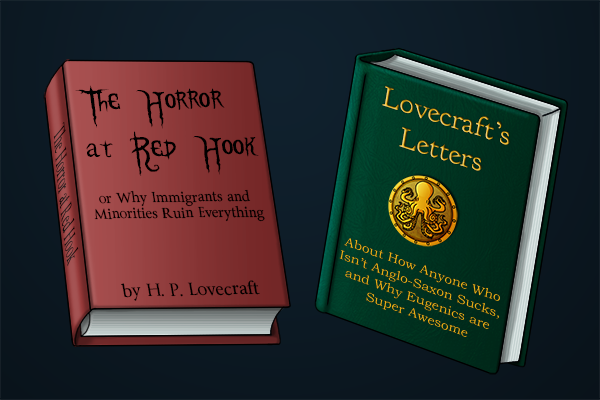

White supremacist Andrew Jackson believed American Indians had “neither the intelligence, the industry, the moral habits, not the desire of improvement” and used this to justify the numerous acts of Cultural Genocide he committed. One of the worst was the Indian Removal Act, which forced the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole to choose between assimilation or leaving their homelands. Justin Giles, assistant director of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Museum, describes it as, “You can have one of two things: you can keep your sovereignty, but you can’t keep your land. If you keep your land you have to assimilate and no longer be Indian… you can’t have both.” While reading The Marrow Thieves, I was struck by how much the world Dimaline created felt like a futuristic Nazi Germany. It makes sense considering “American Indian law played a role in the Nazi formulation of Jewish policies and laws” according to professor of law Robert J. Miller. Good job America, you helped create the Holocaust. I’m sure Andrew Jackson would be proud.

But people tend to object to mass murder and breaking treaties, even in the 1830’s. Jackson’s Indian Removal Act was controversial and drew a great deal of criticism, most notably from Davy Crockett and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Christian missionary and activist Jeremiah Evarts wrote a series of famous essays against the Removal Act that accused Jackson of lacking in morality. So even back then folks hated the 7th president for being a lying, racist piece of shit. Of course that didn’t necessarily mean they were accepting of the people they saw as “savages.” A line from They Called it Prairie Light sums it up best: “Europeans were at first skeptical of the humanity of the inhabitants of the American continents, but most were soon persuaded that these so-called Indians had souls worthy of redemption.” So how could they “kill” Indians without actually killing them and looking like the bad guys? Richard Henry Pratt came up with the solution. Changing everything about Indigenous people to make them as close to Whiteness as possible.

“A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” – Richard Henry Pratt

Pratt was a former Brigadier General who had fought in the Union during the Civil War. He spoke out against racial segregation, lead an all Black regiment known as the “Buffalo Soldiers” in 1867 (yes, the ones from the Bob Marley song), and unlike Jackson, actually viewed the American Indians as people. Unfortunately, like most “White Saviors,” Pratt was ignorant, misguided and believed Euro-Americans were superior. “Federal commitment to boarding schools and their ‘appropriate’ education for Native Americans sprouted from the enduring rootstock of European misperceptions of America’s natives.” (Tsianina Lomawaima). And so Pratt decided the best way to help American Indians was to remove children from their homes to teach them “the value of hard work” and the superiority of Euro-American culture. Pratt had already practiced turning Cheyenne prisoners of war at Fort Marion into “good Indians” and he was convinced an Indian school would be equally successful. So in 1879 he founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, the first Indian boarding school in the US.

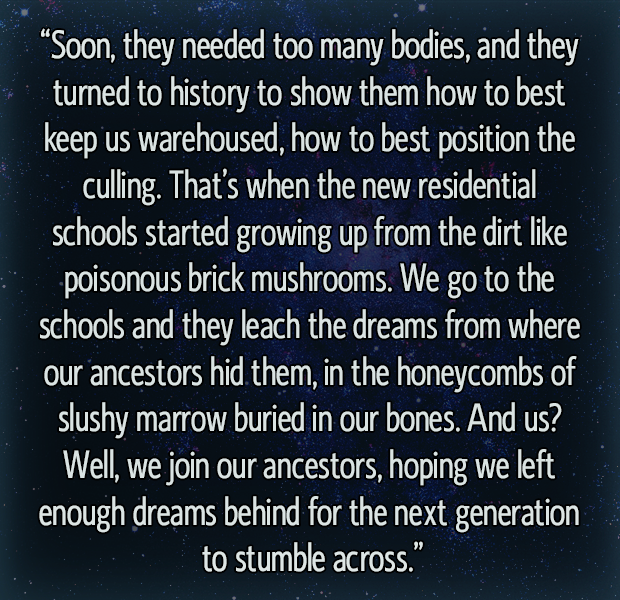

Miig telling the kids how the bone marrow harvesting started.

“Civilizing” American Indian children by separating them from their cultural roots and teaching them Eurocentric values was not a new idea: The Catholic church had already been doing it for years. But it was Pratt who made it widespread. At the school, students were forced to cut their long hair, adopt White names and clothing, speak only in English, and convert to Christianity. Failure to comply would be met with corporal punishment from Pratt, who ran the school like an army barrack. Understandably, Indigenous people — who had no reason to trust a nation of treaty breakers — were initially reluctant to send their children away from their families to go to school. But Pratt convinced Lakota chief Siŋté Glešká aka Spotted Tail (one of three chiefs who had travelled to Washington to try and convince President Grant to honor the treaties the US had made) that an English education was essential to survival in an increasingly Euro-centric America. He argued that if Spotted Tail and his people were able to read the treaties they signed, they never would’ve been forced from their land. He would teach the students so they could return home and in turn help their people. Reluctantly the chief agreed to send the children Dakota Rosebud reservation, including his own sons, to Carlise. Ten years later Pratt’s “save the Indian” goal became a National policy and Natives no longer had a choice in the matter.

“As girls, Martha and young Frances found the atmosphere of the school alien, unfriendly, and oppressive. Both had been raised by nurturing parents of the leadership class, and neither had been abused as a child. They had learned the traditions and laws of their tribes, but the church had not had a strong presence on the San Manuel Reservation. When the girls entered the St. Boniface school, their parents had agreed to their enrollment so that they could cope better with an ever-changing society dominated by non-Indians. Furthermore, their parents expected them to be future leaders of the tribe and felt that training at an off-reservation boarding school would better prepare them for tribal responsibilities.” (Trafzer)

Canada was also pushing for assimilation and, using Pratt’s Residential School model, began to develop their own “off-reserve” schools. In 1920 Duncan Campbell Scott, the Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Canada from 1913 to 1932, passed the Indian Act. The bill made school attendance mandatory for all Indigenous children under the age of 15. Anyone who refused could be arrested and their children taken away by truant officers, the basis for Dimaline’s Recruiters. Residential school survivor Howard Stacy Jones describes how she was snatched by Mounted Police from her public school in Port Renfrew British Columbia and brought to a residential school: “I was kidnapped when I was around six years old, and this happened right in the schoolyard. My auntie and another witnessed this… saw me fighting, trying to get away from the two RCMP officers that threw me in the back seat of the car and drove away with me. My mom didn’t know where I was for three days.”

Scott famously said “I want to get rid of the Indian problem. . . Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill.” Schools in the US and Canada did have some dissimilarities. While the U.S. moved away from mission schools in favor of government run ones, most Canadian residential schools continue to be run by Christian missionaries and supported by several churches. As a result, federal control was weaker in Canada and the goal of converting Indigenous people to Catholicism and Protestantism remained at the forefront. Interestingly, during my research I found that Indigenous people reported a wide variety of experiences in US residential schools ranging from positive to negative, whereas the stories about Canadian ones were overwhelmingly negative. It’s possible that the Canadian residential schools were somehow worse than US ones, possibly due to the strong influence of the state and little government regulation, but I don’t want to draw conclusions on a topic I simply don’t know enough about. Besides it’s not my place to compare the experiences of survivors like that.

Still, I was genuinely surprised to find so many positive memories reported by former US residential school students who felt they benefited from their time there. While conducting interviews for They Called it Prairie Light Tsianina Lomawaima revealed that former Chilocco students had nothing but good things to say about L. E. Correll, the school’s superintendent from 1926 to 1952. “The participants in this research concurred unanimously in their positive assessment of Correll’s leadership, a testimonial to his commitment to students and the school. Alumni references to Mr. Correll… all share a positive tone. He is described as Chilocco’s ‘driving force,’ ‘wonderful,’ [and] ‘a fine man, we called him ‘Dad Correll.'” I bring this up not to minimize the damage the schools did nor excuse the atrocities they committed, but to illustrate the complexity of this topic. It would also be disingenuous not include the wide range of experiences at these schools. Another student at Chilocco wrote a letter to a North Dakota Agency complaining of a broken collarbone and not enough to eat only to be told to stop “whining about little matters.” Another student refused to Chilocco explaining, “I could stay there [at Chilocco) if they furnished clothing and good food. I don’t like to have bread and water three times a day, and beside work real hard, then get old clothes that been wear for three years at Chilocco [sic]. I rather go back to Cheyenne School.”

Regardless, all the schools caused lasting damage to Indigenous culture and communities. What Canada and the US claimed called assimilation “more accurately should be called ethnic cleansing…” explains Dr. Jennifer Nez Denetdale a Najavo Professor of American Studies at the University of New Mexico. Pratt may have had good intentions, but remember what they say the road to hell is paved with. Much like voluntourism today attempts to “help” American Indians through assimilation were rooted in colonialism and hurt more than they helped. Forrest S. Cuch, former director of the Utah Division of Indian Affairs describes the damage done to his tribe, the Utes. “Assimilation affected the Utes in a very tragic way. It was so ineffective that it did not train us to become competent in the White World and it took us away from our own culture, so much so that we weren’t even competent as Indians anymore.” “Children do not understand their language and they’re Navajos. This was done to us.” explained Navajo/Dine elder Katherine Smith. Assimilation was nothing short of Cultural genocide as defined by the 2015 the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada:

“…the destruction of those structures and practices that allow the group to continue as a group. States that engage in cultural genocide set out to destroy the political and social institutions of the targeted group… Languages are banned. Spiritual leaders are persecuted, spiritual practices are forbidden, and objects of spiritual value are confiscated and destroyed. And, most significantly to the issue at hand, families are disrupted to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next.”

Residential boarding schools are yet another atrocity that remains suspiciously absent from American and Canadian history books, but they are popular in Indigenous horror (Rhymes for Young Ghouls, The Candy Meister, These Walls), and for good reason. Survivors describe deplorable living conditions, rampant abuse, rape, starvation, and being torn away from their families and culture. Homesickness was a common problem for young children who had spent their entire lives surrounded by family. Ernest White Thunder, the son of chief White Thunder, became so homesick and depressed he refused to eat or take medicine until he finally died.

“Students arriving at Chilocco [Residential School] met the discrepancies between institutional life and family life at every turn. Military discipline entailed a high level of surveillance of students but constant adult supervision and control was impossible. The high ratio of students to adults and the comprehensive power wielded by those few adults compromised any flowering of surrogate parenting. In the dormitories, four adults might be responsible for over two hundred children. The loss of the parent/child relationship and the attenuated contact with school personnel reinforced bonds among the students, who forged new kinds of family ties within dorm rooms, work details, and gang territories. Dormitory home life-siblings and peers, living quarters and conditions, food and clothing, response to discipline-dominates narratives.” (Tsianina Lomawaima)

Running away was common and could end tragically. Kathleen Wood shared one of her memories of students who ran away: “There were three boys that ran away from [Chuska Boarding School]. They wanted to go home… They were three brothers, they were from Naschitti. They ran away from here as winter… They did find the boys after a while, but the sad part is all three boys lost their legs.” Not everyone survived their attempts to return home, as was the tragic case for Chanie “Charlie” Wenjack (trigger warning for description of child death). At the Fort William Indian Residential School 6 children died and 16 more disappeared.

Indigenous children first entering residential school would often have their long hair cut short, an undoubtedly traumatic experience for many children. For the Cheyenne the cutting of hair is done as a sign of mourning and death. Roy Smith, a member of the Navajo Nation (Diné) where long hair is an essential part of one’s identity, describes his experience: “They all looked at me when they were giving me my haircut… My long hair falling off. And I was really hurt. The teaching from my grandfather was… your long hair is your strength, and your long hair is your wisdom, your knowledge.” Hair is also holds spiritual importance to the Nishnawbe Aski. An anonymous Nishnawbe Aski School survivor was left deeply hurt be her hair cut:

“When I was a girl. I had nice long black hair. My mother used to brush my hair for me and make braids. I would let the braids hang behind me or I would move them over my shoulders so they hung down front. I liked it when they were in front because I could see those little colored ribbons and they reminded me of my mother. Before I left home for residential school at Kenora my mother did my hair up in braids so I would look nice when I went to school. The first thing they did when I arrived at the school was to cut my braids off and throw them away. I was so hurt by their actions and I cried. It was as if they threw a part of me away – discarded in the garbage.” – Anonymous

***Content warning, descriptions of child abuse and sexual assault and an image of verbal abuse of a child below***

Students were severely beaten for not displaying unquestioning obedience and sometimes for no reason at all. Those in charge would constantly reinforce the message that Indigenous people were stupid, worthless, and inferior to Whites, destroying the children’s sense of self-worth. Some students were forced to kneel for long stretches of time, hold up heavy books in their outstretched arms, or locked in the basement for hours. Children would be force-fed spoiled meat and fish until they vomited, then forced to eat their own vomit. Some were even electrocuted. Chief Edmund Metatawabin recalls his experience at St. Anne’s Indian Residential School:

There was [an electric chair with] a metal handle on both sides you have to hold on to and there were brothers and sisters sitting around in the boys’ room. And of course the boys were all lined up. And somebody turned the power on and you can’t let go once the power goes on. You can’t let go… my feet were flying in front of me and I heard laughter. The nuns and the brothers were all laughing.” – Edmund Metatawabin

From 1992 until 1998 Ontario Provincial Police launched an investigation into the abuse at St. Anne’s Residential School after Chief Edmund Metatawabin presented them with evidence of the crimes. The police took statements from 700 St. Anne’s survivors, many of whom described incidents of sexual assault and abuse involving priests, nuns, and other staff. During her interview one survivor said “This shouldn’t have happened to us. They’re God’s workers, they were to look after us.” (link contains graphic descriptions of abuse). One figure estimates that one in five students were sexually abused when attending residential school. But schools would cover up the abuse, and anyone who complained was intimidated into silence.

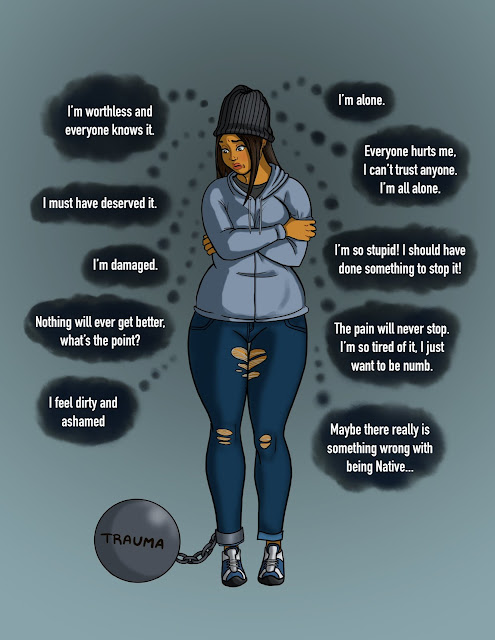

The verbal abuse shown here is paraphrased from actual things said to Residential school survivals. They are taken from interviews and autobiographies. If you or someone you know is being abused, go here. Learn more about forms of abuse here.

All this pain and suffering was committed under the pretense of “civilizing” Native people, when in reality it was Cultural Genocide driven by White supremacy. “The whole move was to make Indian children white… Of course, at the end of the school experience, the children still weren’t white. They were not accepted by White mainstream America. When they went back to their tribal homelands, they didn’t fit in at home anymore either.” says Kay McGowan, who teaches cultural anthropology at Eastern Michigan University. Inuvialuit author Margaret Pokiak-Fenton describes how her mother did not even recognize her when she returned home in her children’s book Not my Girl. As if the rejection wasn’t heart breaking enough, Margaret had forgotten much of her own language and struggled to communicate with her family. Another residential school survivor, Elaine Durocher, says “They were there to discipline you, teach you, beat you, rape you, molest you, but I never got an education…. [instead] it taught me how to lie, how to manipulate, how to exchange sexual favors for cash, meals, whatever the case may be.” In a video for Women’s Centre she volunteers at she discusses how “The teachers were always hitting us because we were just ‘stupid Indians'”.

***End of content warning***

“[People] need to know that it was an event that happened to a lot of kids, that it wasn’t just a few; it was literally thousands of kids that suffered. I’ve come to realize that there were also others where the experience for them was actually very good, and I don’t question that. I can only relate to mine. Mine wasn’t a good one, and I know a lot of really good friends who also did not have a good experience.” – Joseph Williams

In The Marrow Thieves the government and the church join forces to perform experiments on prisoners, and later Indigenous people, in order to find a cure for the dreamless plague. And if you were hoping that was just a metaphor for destroying cultural identities and real residential schools never sunk so low as to experiment on helpless children, well, you’d be wrong. Science has a dark history of exploiting the most vulnerable populations for unethical experiments. In the U.S. alone enslaved women were tortured and mutilated by the father of gynecology without any form of anesthesia (1845-1849), the government backed Tuskegee syphilis experiment (1932-1972) infected hundreds of Black men without their knowledge or consent, a stuttering experiment (1939) performed on orphans is now known as “The Monster Study,” elderly Jewish patients were injected with liver cancer cells (1963) to “discover the secret of how healthy bodies fight the invasion of malignant cells,” and inmates in the Holmesburg Prison were used to test the effects of various toxic chemicals on skin (1951-1974).

In the 1920s experimental eyes surgeries to treat trachoma were conducted on Southwestern US Natives. The contagious eye disease became an epidemic on Southwestern reservations, affecting up to 40% of some tribal groups. “Some tribes, such as the Navajo, experienced no “sore eyes” prior to their defeat by the United States, yet once confined to the reservation, they witnessed a significant increase in unexplained eye problems.” (Trennert) GEE I WONDER WHY. Maybe it had something to do with being forced to live in poverty on shitty reservations where their access to healthcare and sanitation was limited? The government decided to “help” by once again making it worse. The Indian office opened an eye clinic and hired the Otolaryngologist Dr. Ancil Martin to run it. Dr. Martin began the student treatment program before he had any idea how to cure trachoma. He decided to test out a surgical procedure called “grattage” which involved cutting the granules off the eyelids (without anesthesia of coure). One little girl described the experience: “During the operation they cut off little rough things from under the eyelid. It was a grisly scene, with blood running all over. The children had to be held down tight.” (Trennert) Unfortunately the experimental treatment only provided temporary relief and those children who recovered where left with permanent damage to their eyelids. Later, as part of the “Southwestern Trachoma Campaign,” ophthalmologist Dr. Webster Fox convinced the Indian Office to take even more drastic measures and surgically remove the tarsus (the plate of connective tissue inside each eyelid that contributes to the eyelids form and support). His reasoning for this was because he did not believe Indians would submit to prolonged treatment and it was better to “remove the disease more quickly and with less deformity than the way Nature goes about it.” Yikes.

In case you were hoping this was a tragic but isolated incident, I’m afraid I have some bad news for you. When giving testimony to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada survivors consistently described an environment where “hunger was never absent.” Residential school meals were typical low in calories (they ranged from 1000 to 1450 calories per day, undernourishment is considered less than 1,800 calories per day), vegetables, fruit, protein, and fat, all essential parts of a growing child’s diet. “We cried to have something good to eat before we sleep. A lot of the times the food we had was rancid, full of maggots, stink. Sometimes we would sneak away from school to go visit our aunts or uncles, just to have a piece of bannock.” explained school survivor Andrew Paul. Food-borne illnesses were another common occurrence. Although at least partly due to negligence or a lack of funds some schools intentionally withheld food to see how the children’s bodies would react to malnutrition, especially as they fought off viruses and infections. “When investigators came to the schools in the mid-1940s they discovered widespread malnutrition at both of the schools” explained food historian Dr. Ian Mosby. ” “In the 1940s, there were a lot of questions about what are human requirements for vitamins… Malnourished aboriginal people became viewed as possible means of testing these theories.” Mosby said an interview with the Toronto Star. And so Indigenous Canadian children became unwitting guinea pigs in an unethical study. Between 1942 and 1952 Dr. Percy Moore, head of the superintendent for medical services for the Department of Indian Affairs, and Dr. Frederick Tisdall, former president of the Canadian Pediatric Society performed illicit nutrition experiments on students at St. Mary’s School. Milk and dairy rations were withheld. Instead children were given a fortified flour mixture containing B vitamins and bone meal. The experimental supplement impacted their development and caused children to become dangerously anemic, and continued to have negative effects on them as adults. Incidentally, this experimental flour mix was illegal in the rest of Canada.

A decade later the U.S. Air Force’s Arctic Aeromedical Laboratory in Fairbanks wanted to study the role the thyroid gland played in acclimating humans to cold in hopes of improving their operational capability in cold environments. The hypothesis was that Alaskan Natives were somehow physically better adapted to cold environments than White people This is another example of scientific racism as the study didn’t bother looking at the White inhabitants of the Arctic Circle: Greenlanders, who hypothetically should have a similar resistance to the cold. Instead, they chose to focus on Alaskan Natives almost as if they were a different species. The othering didn’t end there. Participants (84 Inuit, 17 Athabascan Indians, and 19 White service members) were given a medical tracer, the radioisotope iodine 131 to measure thyroid function. Guess who wasn’t told they were part of the experiment? Instead of informing the Indigenous test subjects they were participating in a research study as would’ve been required by the recently created Nuremberg Code (the first point in the code literally says “The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential”), the scientists just said “Fuck it, we do what we want!” I mean, it’s not like someone might want to know they were being given RADIOACTIVE MATERIAL or anything right? Not only did the experiment offer no potential benefit to the Alaskan Natives who participated but the original hypothesis was disproven. The Airforce provided no follow up tests or treatment for the test subjects to insure they hadn’t suffered any long-term effects.

Students at Kenora residential school were used as test subjects for ear infection drugs, again without their knowledge or consent. School nurse Kathleen Stewart wrote in her report “The most conspicuous evidence of ear trouble at Cecilia Jeffrey School has been the offensive odor of the children’s breath, discharging ears, lack of sustained attention, poor enunciation when speaking and loud talking,” In a follow-up report she noted three children “were almost deaf with no ear drums, six had [hearing in] one ear gone.”

Human research violations aren’t just a problem of the distant past before the IRB was established. In 1979 Native leaders asked researchers to help them assess the drinking problem in their community in Barrow, Alaska. They were hoping to cooperate with them to find a solution. Instead the researchers went ahead and publicly shared the results of the Barrow Alcohol Study with news outlets. Because the study implied the majority of adults in Barrow were alcoholics (which was inaccurate), left out the socioeconomic context which led to drinking problems, and then announced the results without representatives from the tribal community, it caused both a great deal of shame and direct financial harm. Starting in the 1990s, Arizona State University obtained blood from the Havasupai tribe under false pretenses. Instead of using the samples for diabetes research like they had promised the tribal members, researchers used the Havasupai’s DNA for a wide range of genetic studies. This continued until 2003 when a Havasupai college student discovered how the blood was being used without permission. Carletta Tilousi explained in an NPR Interview “Part of it is it was a part of my body that was taken from me, a part of my blood and a part of our bodies as Native-Americans are very sacred and special to us and we should respect it.”

Keeping all this in mind the dystopian future that Dimaline created suddenly doesn’t seem so far-fetched. Indigenous people have already had their land stolen, their graves robbed, their children kidnapped, and their culture appropriated. They’ve even had their blood taken under false pretenses. Indigenous children held prisoner in residential schools were deliberately starved and denied access to basic healthcare all in the name of science. The Marrow Thieves feels especially poignant right now, with the Americas experiencing (at the time of writing this) some of the highest Covid-19 rates in the world. Who would we sacrifice to find a cure? Pfizer, the company responsible for making one of the two currently available Covid vaccines did illegal human research as recently as the 90’s. “What does it mean when the disproportionate disease burden currently faced by Indigenous communities is, in large part, the product of a residential system that the TRC has found was nothing short of a cultural genocide?” asks Mosby. “In part, it means that we need to rethink the current behavioral and pharmacologic approaches… in Indigenous communities. In their place, we need more community-driven, trauma-informed and culturally appropriate interventions… [and] also acknowledge the role of residential schools in determining the current health problems faced by residential school survivors and their families…[M]ost importantly, we need to demand that the next generation of Indigenous children have access to the kinds of plentiful, healthy, seasonal and traditional foods that were denied to their parents and grandparents, as a matter of government policy” he argues.

The worst part about the residential school is that even after they closed, their legacy remained and the damage they did would affect future generations. A report entitled Indigenous Communities and Family Violence: Changing the Conversation states “The [Royal Commission on Aboriginals Peoples] named residential schools as a significant cause of family violence in Indigenous communities… and the intergenerational impacts of residential schools on the prevalence continues to be recognized…”. Many of the abused students became abusers themselves, taking out their pain, fear, and frustration on the younger children. After leaving the school, survivors continued to suffer from low self esteem, hopelessness, painful memories and severe mental, social, and emotional damage. Boarding school trauma was then passed down from parent to child and the cycle of abuse would continue. Because the children were deprived of affection and family during their formative years, many of them left residential school emotionally stunted and unable to openly express love, even towards their own children.

“Few [students] came out of residential schools having learned good boundaries, and good boundaries included some sense of self-determination, sovereignty over your own body. They didn’t have any control over that, and they didn’t see people around with appropriate behavior and being respectful of them as human beings, that they were sacred. And they were abused. Children learn what they live and that was their life.” – Sylvia Maracle, executive director of the Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres.

Add in loss of land, racism, poverty, and a lack of healthcare and support and you’re left with a complex system of trauma that’s stacked against Indigenous people and their recovery. A report prepared for the Aboriginal Healing Foundation entitled Aboriginal Domestic Violence in Canada states:

“Social and political violence inflicted upon Aborigional children, families and communities by the state and the churches through the residential school system not only created the patterns of violence communities are now experiencing but also introduced the family and community to behaviors that are impeding collective recovery.”

In her award-winning autobiography They Called Me Number One writer and former Xat’sull chief Bev Sellars discusses the long-lasting damage to her done by St. Joseph’s Mission. Sellars watched helplessly as her brother’s personality completely changed as a result of sexual abuse and he began to take out his rage and pain on her. Sellar’s own trauma affected the way she interacted with her three children. She practiced an authoritarian style of parenting she had learned from the school and expected her children to hide their pain instead of expressing it as she was forced to do. Because the only touch Sellars experienced at the residential school was painful and abusive she feared any form of physical contact and was unable to hug anyone until her own children were grown. She continued to fear disobeying any White person or authority figure and made her want her children to behave perfectly in front of Whites.

She describes how she suffered from panic attacks, migraines, nightmares, memory problems, emotional numbness, angry outbursts, shame and phobias after attending the residential school. Because her complaints of mistreatment were dismissed and summarily punished by those in charge, Sellars developed a learned helplessness and “why bother?” attitude. Years of brainwashing by the nuns and priests caused Sellars to see “the world through the tunnel vision of the mission” and led her to believe she was inferior because she was Indigenous. Those familiar with trauma will recognize these as PTSD symptoms commonly seen in survivors. Unfortunately, emotional and mental health were still poorly understood in the 1960s and medical services are limited on reservations forcing survivors like Sellars to find other ways to numb their pain.

***Content warning for image of depressive thoughts below***

The ball and chain represent the trauma the residential school survivor has to carry around with her. Her thoughts are based on those common to people with trauma. Please contact a mental health provider (listed at the beginning and end of the review) if you have similar thoughts.

***End of content warning***

In The Marrow Thieves Wab eventually shares how her mother became addicted to alcohol and later crack cocaine. The stress of living in a dirty, overcrowded military state while trying not to starve or get taken away by the school staff became too much for her. Wab wonders if her mother could feel herself dying and just gave up. Alcohol and drugs are frequently abused by those who’ve experienced trauma or have untreated mental illness. In fact, childhood abuse is prevalent among alcoholics, and children who experience trauma are four to twelve times more likely to engage in substance abuse. Sellars’ brother never recovered from the sexual abuse he experienced at the hands of the priests and developed an addiction to alcohol. Others survivors die by suicide. According to the CDC the suicide rate among adolescent American Indians is more than twice the U.S. average and the highest of any ethnic groups. Amanda Blackhorse explains “…we’re still feeling the effects of boarding schools today… and it has completely demolished the Indigenous familial system. And many of our people are suffering and they don’t… realize that they are suffering from the boarding school system. Many of us don’t even understand it…”

However, while alcoholism is definitely a problem in Native populations the stereotype of the “drunken Indian” is no more than a harmful myth. Indigenous people aren’t “genetically more susceptible to alcoholism” and American Indians are actually more likely to abstain from alcohol that Whites.

“The participants in this study talked about historical trauma as an ongoing problem that is at the root of substance abuse issues in their families and communities. Further, the participants believed their experiences to be shared or common among other AI families and communities. Feelings about historical trauma among the participants, their families, and/or their communities included disbelief that these events could have happened, sadness, and fear that such events could recur; however, there also were messages about strength and survival.” – Laurelle L. Myhra

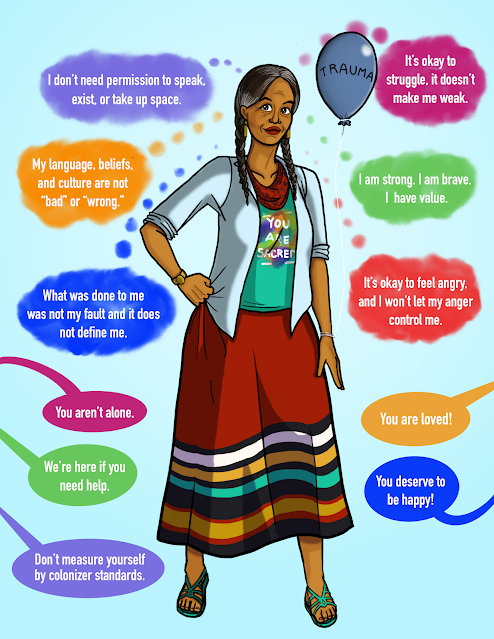

This huge, horrible thing that scarred thousands of survivors and had long lasting effects for Indigenous populations is almost entirely unknown outside of Native, Inuit and Métis communities, and the Canadian Government continues to underfund education and health services for Indigenous children. But there are many Indigenous people, like Bev Sellars, who are not just surviving, but flourishing, and in turn helping others to recover. Indigenous founded and run groups such as The National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center, Freedom Lodge, Indigenous Circle of Wellness, and Biidaaban Healing Lodge, are all working to heal generational trauma by combining traditional Indigenous healing practices and modern trauma-informed therapy to create a holistic approach to wellness and mental health. Horror and Apocalyptic Fiction has also given Indigenous creators a way to process this generational trauma and make a wider audience aware of these historical atrocities. But even with everything Indigenous people have suffered through, they’re still here. The Marrow Thieves similarly ends on a hopeful note with Frenchie and his friends holding their heads high as they march into the future.

The girl from the residential school is all grown up, and with the support from her community has started to heal. Her trauma, now represented by a balloon to show the “weight” of it is now gone, is still there but is no longer impeding her ability to enjoy life. She finally feels free to celebrate her Chippewa culture and heritage, as reflected by her bright clothing and long braids. Her T-shirt is from Choctaw journalist and artist Johnnie Jae’s collection. Her skirt is based on the work of Chippewa fashion designer Delina White. Her scarf has a floral Chippewa design.

Sources:

Unspoken: America’s Native American Boarding Schools, PBS, 2016

The Indian Problem, The Smithsonian, 2016

In the White Man’s Image, PBS, 1992

Bopp, J., Bopp, M., and Lane, P. Aboriginal Domestic Violence in Canada. The Aboriginal Healing Foundation. 2003. https://epub.sub.uni-hamburg.de/epub/volltexte/2009/2900/pdf/aboriginal_domestic_violence.pdf

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. An Indigenous People’s History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2014.

Fortunate Eagle, Adam. Pipestone: My Life in an Indian Boarding School. University of Oklahoma Press, 2010.

Health Justice, Daniel. Why Indigenous Literature Matters. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018.

Holmes, C. and Hunt, S. Indigenous Communities and Family Violence: Changing the Conversation. National Collaborating Center for Aboriginal Health, 2017. https://www.nccih.ca/docs/emerging/RPT-FamilyViolence-Holmes-Hunt-EN.pdf

Jordan-Fenton, C. and Pokiak-Fenton, M. Not My Girl. Annick Press, 2014.

Jordan-Fenton, C. and Pokiak-Fenton, M. Fatty Legs. Annick Press, 2010.

Mihesuah, Devon A. American Indians Stereotypes & Realities. 1996. Reprint. Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2009.

Mihesuah, Devon A. So you Want to Write About American Indians?: A Guide for Writers, Students, and Scholars. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Pember, Mary Annette. “Death by Civilization.” Atlantic, 8 March. 2019.

https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2019/03/traumatic-legacy-indian-boarding-schools/584293/

Robertson, David Alexander. Sugar Falls: A Residential School Story. Highwater Press, 2012.

Sellars, Bev. They Called Me Number One: Secrets and Survival at an Indian Residential School. Talonbooks, 2013.

Sterling, Sherling. My Name is Seepeetza. Groundwood Books, 1992.

Trafzer, C. E., Keller, J.A., eds. Boarding School Blues: Revisiting American Indian Educational Experiences. Bison Books, 2006.

Treuer, Anton. Everything You Wanted to Know about Indians But Were Afraid to Ask. St Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012.

Tsianina Lomawaima, K. They Called It Prairie Light: The Story of Chilocco Indian School. University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

Robinson-Desjarlais, Shaneen (host). Residential Schools Podcast Series. Audio podcast, February 21, 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/residential-schools-podcast-series

Dawson, Alexander S. “Histories and Memories of the Indian Boarding Schools in Mexico, Canada, and the United States.” Latin American Perspectives 39, no. 5 (2012): 80-99. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41702285.