Formats: Print, digital

Publisher: Tor

Genre: Body Horror, Eldritch, Monster, Occult, Psychological Horror, Sci-Fi Horror

Audience: Young Adult

Diversity: Queer character (Gay woman), POC characters (Black, Creole woman, unknown POC character), Bisexual author, Malaysian author

Takes Place in: London

Content Warnings (Highlight to view): Alcohol Abuse, Body-Shaming, Bullying, Child Abuse, Child Endangerment, Death, Gore, Pedophilia, Physical Abuse, Racism, Rape/Sexual Assault, Sexism, Sexual Abuse, Slurs, Slut-Shaming, Verbal/Emotional Abuse, Violence

Blurb

John Persons is a private investigator with a distasteful job from an unlikely client. He’s been hired by a ten-year-old to kill the kid’s stepdad, McKinsey. The man in question is abusive, abrasive, and abominable.

He’s also a monster, which makes Persons the perfect thing to hunt him. Over the course of his ancient, arcane existence, he’s hunted gods and demons, and broken them in his teeth.

As Persons investigates the horrible McKinsey, he realizes that he carries something far darker. He’s infected with an alien presence, and he’s spreading that monstrosity far and wide. Luckily Persons is no stranger to the occult, being an ancient and magical intelligence himself. The question is whether the private dick can take down the abusive stepdad without releasing the holds on his own horrifying potential.

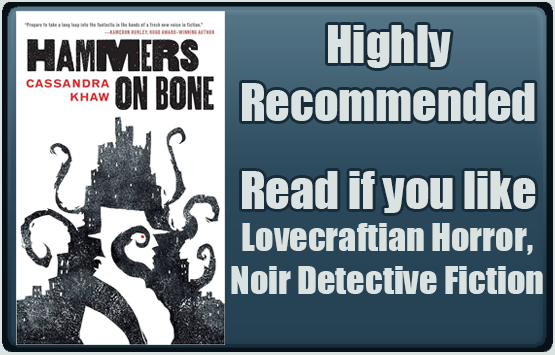

During one of my late-night explorations of the internet (when I should have been sleeping but was instead googling all the random thoughts that pop into my head at 2 AM) I stumbled upon the work of Malaysian author Cassandra Khaw, a nerdy, queer woman who writes video games and short horror stories. Instantly intrigued, I purchased one of her novellas, Hammers on Bone, and I have to say, I fell absolutely, head-over-heels in love with Khaw’s writing. Her beautifully crafted stories are full of wonderful words like “penumbra” and “ululation” (one of my favorite Latin derived words), deliciously grotesque descriptions, and unique characters. English is Khaw’s third language, yet she uses it with a mastery that puts even native English speakers to shame. Her writing has a lot of range, too. These Deathless Bones is a feminist fairy tale about a witch getting sweet revenge on her wicked stepson. Rupert Wong, Cannibal Chef is a comedic splatterpunk series, as hilarious as it is gory, about the misadventures of the titular chef who prepares decadent meals of human flesh for gods and ghouls and gets wrapped up in international deity politics. Khaw has even dabbled in chick-lit (while also managing to poke fun at the more problematic elements of the genre) with her book, Bearly a Lady, about a bisexual, plus size wear-bear that works at a faerie-run fashion magazine. Then there’s her Persona Non Grata series. Much like Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom, Khaw’s novellas take place in a Lovecraft inspired universe, but she flips the famously racist HP the bird by putting people of color at the forefront and using his creations to address social issues like racism, poverty, and abuse. Both stories feature the private investigator, John Persons, one of the most interesting characters I’ve come across in horror fiction. It’s the first of Person’s two novellas, Hammers on Bone, that I’ll be reviewing here.

Persons speaks and acts like the “hardboiled detective” characters from 1930s pulp magazines, complete with dated American vernacular and machismo, despite living in modern day London. This makes John seem incredibly out of place and occasionally downright ridiculous, like when he describes a little boy running into his arms for a hug as “crashing into me like a Russian gangster’s scarred-over fist.” When he’s not working as a PI, John spends his time saving the world from destruction by Star Spawn and Elder-Things. He’s adept at using magic, smokes cigarettes to dull his inhumanly strong sense of smell, enjoys the cold, and can pick up memories from objects and people through physical contact. He also happens to be a Dead One (though not one of the Great Old Ones, Persons is quick to explain), an otherworldly creature whose true, terrifying form comfortably possesses resides in a human body which he shares with the ghost of its previous inhabitant. I bet that’s why he has the most unimaginative, made-up sounding name ever; it was probably the first thing that popped into his head when he started inhabiting his meat suit.

Persons and his human body have an interesting relationship, more commensal than parasitic. While other Star-Spawn and Elder Things simply take what they want, invading human flesh like a disease and eventually destroying their hosts, Persons tries to minimize damage to his meat suit (he may be immortal and resilient, but his human form still suffers from wear and tear, and he feels pain when it’s damaged), and gives his phantasmal passenger a say in certain decisions. Even though he’s in the driver’s seat, John’s body will still react to its original owner’s thoughts and feelings, independent of him. In one scene, the meat suit becomes aroused by the proximity of a beautiful woman. Persons is aware of “his” body’s quickening pulse and rising temperature (among “other” rising things, heh), and states that the sensation is “not unpleasant”, but he describes the physical reaction with the detached interest of scientist observing a cell under a microscope. He is, after all, still an alien being.

Not much is known about the man whose skin he now wears, except that he’s an older person of color who lived during the interwar period, and gave John his body willingly after being asked. The whole Philip Marlowe / Sam Spade persona Persons adopts to appear more human is as an homage to his meat suit’s original owner. I guess it’s kind of sweet that he does that, in a very weird way, but unfortunately his stubborn refusal to update his dated vocabulary and attitudes, or venture into any genre that isn’t detective noir makes John come off as pretty sexist. He refers to women as “skirts,” “broads,” “dames,” and “birds”, and divides them into victims and femme fatales. This attitude backfires on him spectacularly since, of course, the real world isn’t like his detective novels, and John keeps misjudging the women he interacts with.

What sets the monstrous PI apart from his fellow cosmic entities, besides seeking consent from his body’s original owner, is his fondness for humanity, his dedication to following the law and maintaining order, and his desire for earth to remain more or less the way it is, i.e. not a barren hell-scape inhabited by Eldritch abominations. Most of the monsters he fights are chaotic evil, infecting and destroying whenever they go, but John Persons is closer to lawful neutral, occasionally leaning towards good. He’s not exactly heroic since, in his words, “Good karma don’t pay the bills,” but Persons does have a strong set of morals. As previously mentioned he’s big on consent and describes the act of possessing a willing host’s body as “better than anything else I’d ever experienced” and feels incredibly guilty when he accidentally reads a woman’s mind after touching her arm. When she becomes understandably angry at the violation, screaming “You don’t take what you’re not given!” John doesn’t try to minimize, excuse, or defend his behavior (even though the intrusion was an accident), he simply apologizes, mortified by what he’s done. He can even show compassion at times, but how much of his altruistic behavior is due to the remaining sentience of his body’s former inhabitant acting as his ghostly conscience is unclear.

It’s his spectral companion who convinces John to take the case of a young boy named Abel, who wants Persons to kill his abusive stepfather. While initially hesitant about committing murder, John is convinced once the boy reveals that his stepfather is a monster, both literally and figuratively, and both Abel and his little brother’s lives are in danger. He might not be a hero, but Persons does seem to genuinely want to help the two boys, even if he claims it’s just because they’re clients. It may be simply because he wants the ghost with whom he cohabitates to stop nagging him, as John is usually pretty indifferent to human suffering on his own, or perhaps it’s because an Old One is involved, and he’d really prefer it not destroy the world. Regardless of the reason, he agrees to help.

In his eagerness to play white knight (or his meat suit’s eagerness) Persons often fails to realize that the “helpless victims” he seeks to rescue are often perfectly able to take care of themselves, like the waitress whose mind he reads. He’s also quick to victim blame the boys’ mother for not leaving, clearly unable to understand the psychological element of abuse or how dangerous it is for a person to try and leave an abusive partner, just making her feel worse than she already does. John struggles when it comes to comforting victims or dealing with their emotions. He claims his lack of skill when it comes to words and feelings is due to being a “man” (or at least inhabiting the body of one), though it’s just as likely it’s because he’s an eldritch abomination, and he’s just been using sexism to avoid learning the nuances of human emotion. While Persons is better at managing his desire to destroy and devour than the other monsters and is able to maintain a detached control over his meat suit’s emotions and baser instincts, he’s not immune to the effects of his human body’s testosterone or his own toxic misogyny. When the PI is feeling especially aggressive his true form starts to writhe beneath his human skin, straining to break free from his epidermis and rip apart the object of his ire. Even his thoughts start to degrade into a sort of violent, inhuman, babble when he gets too riled up. John actually has to fight to keep control of his monstrous body when he first encounters the abusive stepfather, he’s so desperate to disembowel and devour him. His true nature is a stark contrast to the cool and logical detective persona Persons has adopted. I won’t lie, I did enjoy seeing him act all protective of Abel and his little brother. There’s something amusing about what is essentially an immortal abomination that can effortlessly rip a grown man in two, doing something as mundane and sweet as escorting his young client home while carrying the child’s kid brother on his hip. It’s also heartbreaking when you realize the two boys are safer with a literal monster than their step dad, McKinsey (even before he was possessed).

The step-father is a real piece or work, and throughout the story I desperately wanted John to give in to his monstrous instincts and tear the bastard apart, limb by limb. But being a man/monster of the law, Persons won’t do much more than saber-rattle until he has solid proof of McKinsey’s wrong doing, much to Abel’s frustration. The kid would much rather the PI solve things with his fists (teeth, tentacles, claws, and other miscellaneous alien appendages) than waste time talking to witnesses, and I’d certainly be annoyed too if the monster I hired to kill someone wasted time playing detective instead of just eating his target. But Persons did warn Abel that he’s not a killer for hire and wants to do things “by the book”. Unfortunately, like most real monsters, McKinsey excels at hiding his wrong doing and camouflaging his true nature which makes it difficult for John to find a solid lead. People like McKinsey and describe him as a “loving family-man”. Those who haven’t been completely conned by his act either don’t care he’s a monster (like his boss) or are too terrified to do anything (like his fiancée). None of the adults in the boys’ lives are fulfilling their duty of protecting two vulnerable children. This is where the real horror lies in Khaw’s story– not the eldritch abominations like Shub-Niggurath, or the threats of world destruction, but the all too painful reminder that we so often fail abuse victims. Khaw is tasteful when describing what the two boys go through, and it isn’t played for titillation or described in explicit detail. She only reveals enough to lets us know the two boys in the story are going through something no child should ever have to suffer. I also liked her choice to make the victims male. Far too often male survivors are overlooked, erased, or mocked because society tells us males can’t be victims, even though the CDC states that “More than 1 in 4 men in the United States have experienced rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime” and a study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine found that 1 in 6 boys will be sexually abused before the age of 18. As depressing as these statistics are, the situation isn’t completely hopeless, because monsters aren’t invulnerable, even the kind that have been infected by Elder Things. As Person muses towards the end of the book “I don’t remember who said it, but there’s an author out there who once wrote that we don’t need to kill our children’s monsters. Instead, what we need to do is show them that they can be killed.” For those of us who can’t go out an hire a eldritch abomination PI, at least we have RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network) and their recommended resources for cases of abuse and sexual assault.