Formats: digital

Publisher: Self published

Genre: Ghosts/Haunting, Monster, Occult, Romance, Vampire, Werewolf, Zombie

Audience: Y/A

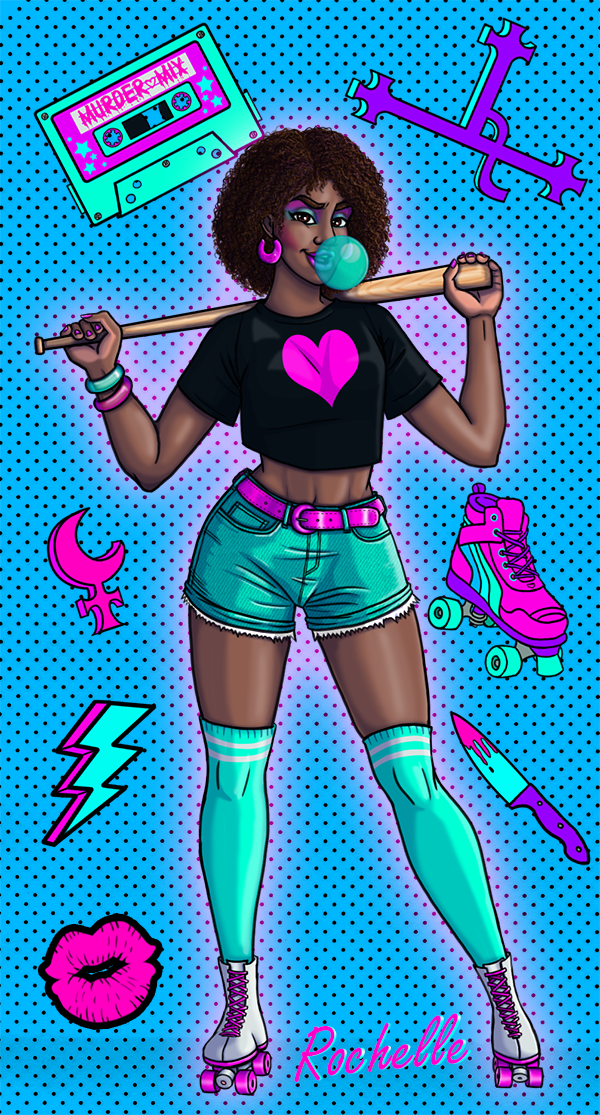

Diversity: Bisexual main character, non-binary minor character, Black major character

Takes Place in: LA, California

Content Warnings (Highlight to view): Alcohol Abuse, Cannibalism, Death, Forced Captivity, Gaslighting, Gore, Medical Procedures, Mental Illness, Racism, Sexism, Slurs, Slut-Shaming, Violence, Vomit, Xenophobia

Blurb

Determined to pass junior year, Logan won’t let Henry distract him—much. Logan’s focusing on all things human, which means his swoony vampire ex-boyfriend will have to file his own fangs for a change. When he goes to the school bonfire and runs into Henry, wandering into the woods seems like a great escape. Until he’s bitten by a wicked Crone with some twisted magical munchies.

Logan is certain his ex-free human future is done when he’s dragged off to a scientific institution for study. There, he’s presented with an opportunity to keep his life, family, and future. All he has to do is stick to human ideology, since all things paranormal are illegal. But complications arise when the Crone begins to haunt him and Logan realizes that if he wants to get his life back, he has to navigate his lingering feelings for Henry.

With the Crone set on devouring him and the institution ready to obliterate him for any missteps, Logan must decide between pursuing the human future his family wants—one that he thought he wanted too—or the chance to embrace Henry, even if the world isn’t ready.

I received this product for free in return for providing an honest and unbiased review. I received no other compensation. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.

Logan just wants a safe, normal, drama-free junior year, and that means avoiding his vampire ex, Henry, at all costs. Which is easier said than done. Logan may be shy and awkward, but Henry is his complete opposite: confident, outgoing, and suave. When his best friend Kiera (a phantom) drags him to a bonfire party that’s supposed to help Logan relax, he discovers that trouble has a way of following him. Not only is Henry there, but Logan is attacked (for the second time since he first started dating Henry) by a powerful creature, this time a monstrous witch known as the “Crone.” After sustaining a bite from the Crone, Henry’s life changes forever.

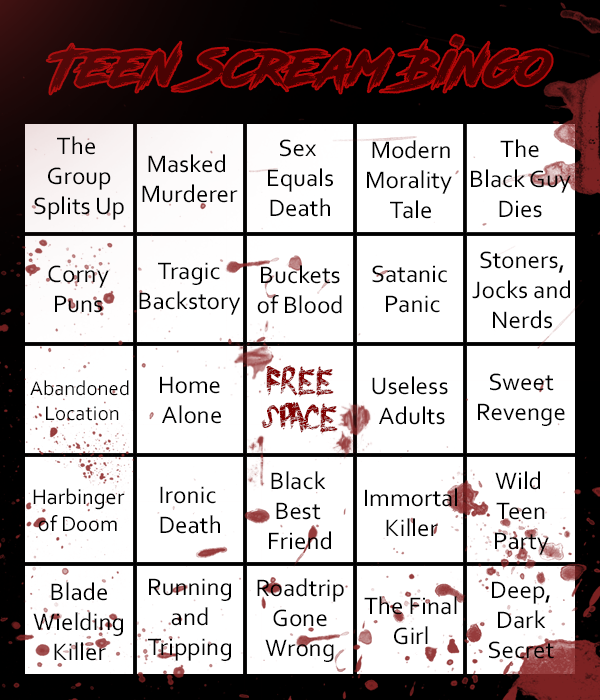

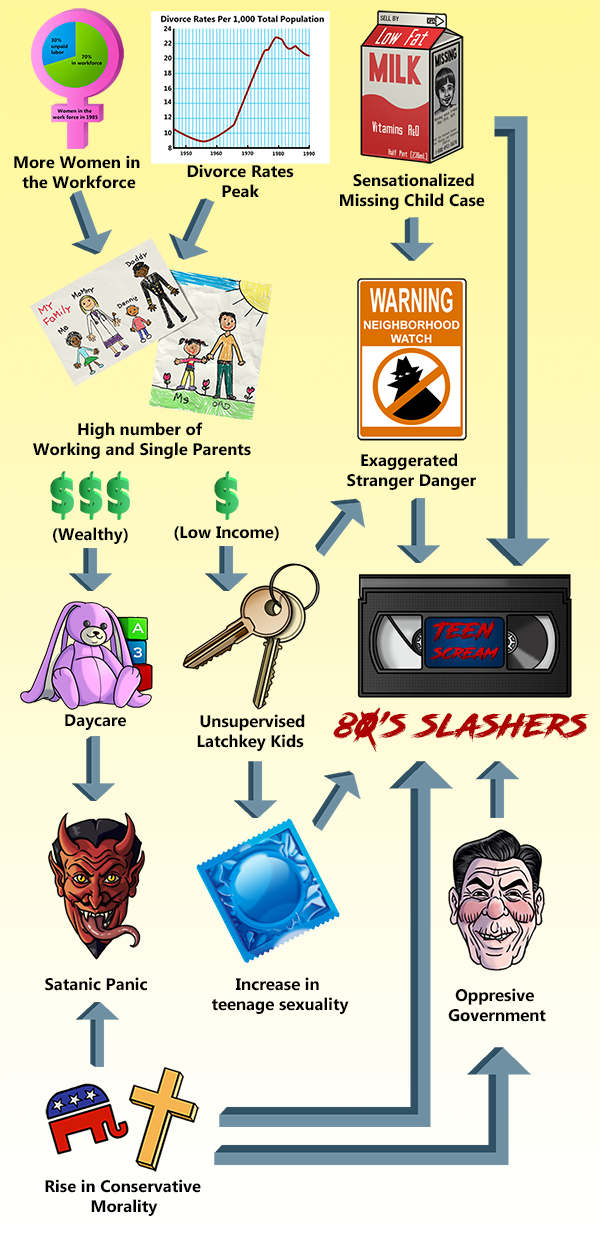

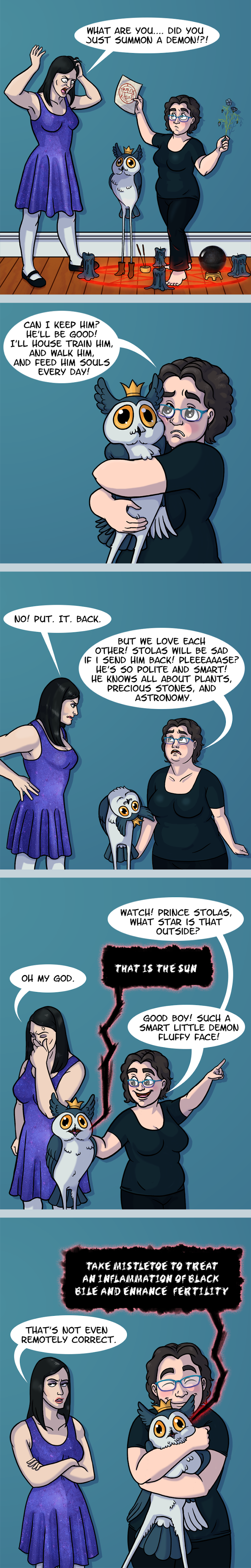

Henry and Kiera are known as Vices, a group of monsters including phantoms, witches, vampires, trolls, sirens, and werewolves that are forced to live in the shadows due to public fear and draconian laws. The Crone is a sin, a powerful Vice that feeds on other Vices and can turn humans into undead monstrosities called Hauntings (think zombies and ghouls) with a single bite. After Henry’s attack he’s whisked away by SPU agents (the special police force in charge of catching and neutralizing Sins) to a secure facility designed to treat Hauntings, but to everyone’s surprise he doesn’t transform into a Haunting. It turns out Henry is a rare form of Vice, known as a Viceling, more human than Vice. The lore of Crescentville Haunting can get confusing in places, and there’s a lot of backstory. So much so that I actually checked to see if there was a prequel I had missed. But it’s no worse that any other fantasy novel with rich world building. If you can remember the rules of Quidditch, you can remember the magical classification system Bennet has created.

The characters are relatable and their voices sound authentic. The romance is steamy without being explicit and felt age appropriate for younger teens. It should be noted that while the book contains a paranormal romance, it’s not the central theme of the story. Instead, we focus on Logan’s struggles with his new identity and trying to fit into a human-centric world– an analogy for trying to fit into a heteronormative society when you’re LGBTQIA+. In Monsters in the closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film Harry M. Benshoff writes “monster is to ‘normality’ as homosexual is to heterosexual.” LGBTQIA+ scholars have long equated queerness with fictional monsters and stories like Crescentville Haunting reclaim the “monstrous queer.” In Bennett’s story, the “homosexual vampire” is the hero rather than the villain, with the humans representing an oppressive heteronormative society and the facility attempting to “cure” Logan of his monstrousness a metaphor for conversion therapy. In addition to romance, the book also has plenty of horror, violence, and suspense, all courtesy of the Crone who continues to haunt Logan after the initial attack.

Overall, this was a fun read with a good world building, a cute relationship, and teens who actually sounded and acted like teens.