Formats: Print, digital

Publisher: Unnerving Magazine

Genre: Killer/Slasher, Myth and Folklore, Occult, Demons

Audience: Y/A

Diversity: Black main character and author, Native Oglala Lakota main character, character with syndactyly

Takes Place in: Florida, USA

Content Warnings (Highlight to view): Abelism, Alcohol Abuse, Animal Death, Child Abuse, Death, Forced Captivity, Gore, Kidnapping, Physical Abuse, Racism, Sexual Abuse (Voyeurism), Slurs, Slut-Shaming, Torture, Verbal/Emotional Abuse, Violence

Blurb

The summer of 1989 brought terror to the town of Shadows Creek, Florida in the form of a massacre at the local carnival, Cirque Berserk. One fateful night, a group of teens killed a dozen people then disappeared into thin air. No one knows why they did it, where they went, or even how many of them there were, but legend has it they still roam the abandoned carnival, looking for blood to spill.

Thirty years later, best friends, Sam and Rochelle, are in the midst of a boring senior trip when they learn about the infamous Cirque Berserk. Seeking one last adventure, they and their friends journey to the nearby Shadows Creek to see if the urban legends about Cirque Berserk are true. But waiting for them beyond the carnival gates is a night of brutality, bloodshed, and betrayal.

Will they make they it out alive, or will the carnival’s past demons extinguish their futures?

I received this product for free in return for providing an honest and unbiased review. I received no other compensation. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.

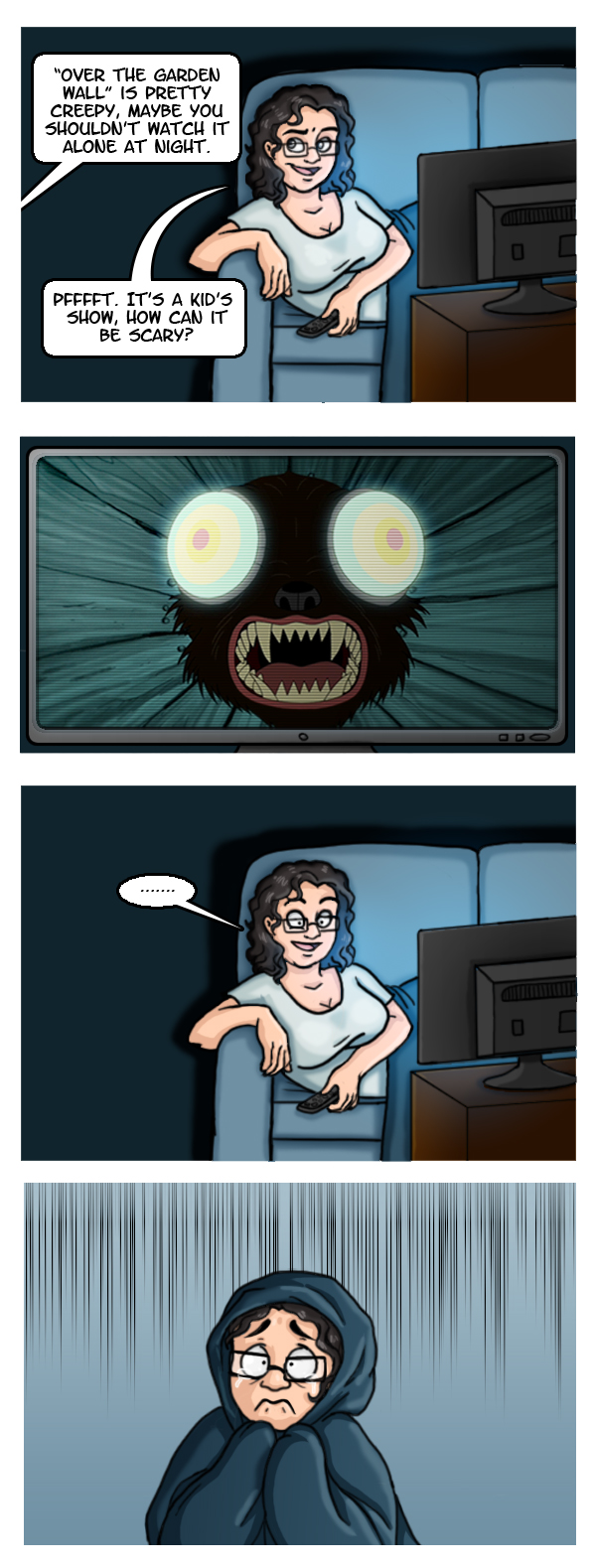

Put on your sequins and neon spandex, grab a New Coke, and turn up that Whitney Houston cassette because it’s time to take a look at Jessica Guess‘s tribute to eighties’ slashers, Cirque Berserk! Guess’s new horror novella is the perfect ode to trashy, B-horror movies of the yuppie decade à la The Funhouse, Evilspeak, and Prom Night. Praised by one of my favorite horror authors, Stephen Graham Jones, Cirque Berserk hits most of the squares on the “teen scream” Bingo card, but still feels fresh and original. Guess has fun playing with the classic slasher clichés while subverting more problematic tropes like the “black best friend” and the “nice guy” being rewarded with a hot girl. She fills her story with plenty of self-aware humor and the kind of affectionate mocking that can only come from a true horror fan, which balances well with the more serious scenes of racism, sexism, and abuse. The result is a fun, nostalgic, carnival ride with a deeply emotional narrative hidden just beneath all the glitter, gore, and a bad-ass Black protagonist.

The eighties have made a come back in horror recently with popular TV shows (Stranger Things, American Horror Story: 1984), movies (the It reboot, The Final Girls), and novels (Grady Hendrix’s My Best Friend’s Exorcism) all drawing inspiration from the decade that gave rise to the slasher film, and it’s no wonder why. Not only do they have the nostalgia factor going for them as Gen Xers have their midlife crises, but they’ve got a ton of amazing source material to work from. Eighties audiences were blessed with a plethora of classic horror movies: grotesque monsters (The Thing, Aliens, Scanners, American Werewolf in London), final girls who fought back, (Halloween, Nightmare on Elm Street, Hell Raiser, Aliens), self-aware humor (Elvira, Monster Squad, Fright Night) cool, sexy vampires (Lost Boys, Near Dark, The Hunger) and horror franchises (Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Friday the 13th, The Evil Dead) graced the silver screen. Hell, even the remakes were good. Both The Fly and The Thing arguably surpassed their originals.

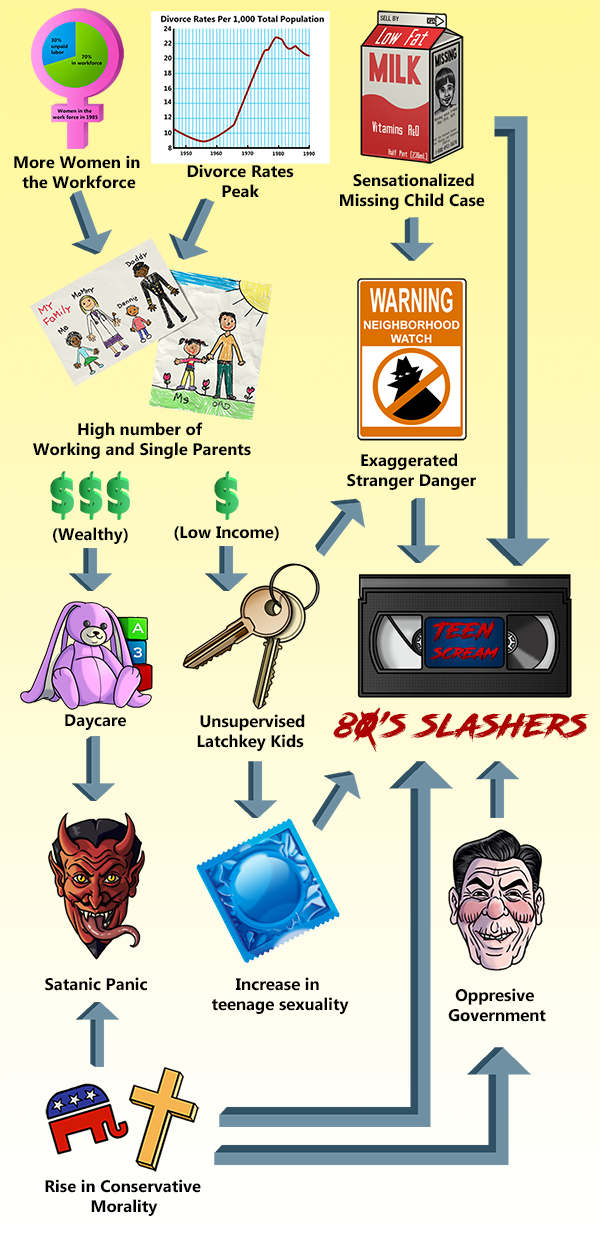

But what was it about the decade of greed that inspired so many amazing films? To understand eighties horror, you need to understand that the 1980’s were an age of excess, greed, rapid technological advancement, and reactionary conservatism. As late writer/director Stuart Gordan explained in the Shudder documentary In Search of Darkness: A Journey Into Iconic 80’s Horror, “horror thrives when there’s a repressive government” and the Reagan years certainly qualified. Additionally, public uncertainty and fear lead to the genre’s rise in popularity, just as it did during the Great Depression resulting in Universal’s famous Golden Age monsters. Meanwhile, advancements in technology and the increased affordability of personal computers led to some groundbreaking special effects and makeup (The Thing, Scanners, The Fly, American Werewolf in London). This decade was the perfect balance of repression and paranoia for horror films to flourish.

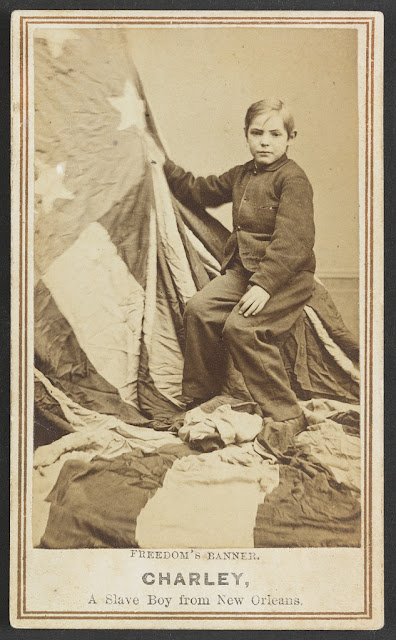

The rise of the “New Right” in the late seventies and eighties brought with it a push to return to “traditional American values” (i.e. being sexist, racist, homophobic, and slut-shaming with impunity). Everywhere you looked, the crack cocaine epidemic was sweeping the nation, AIDS was desolating the population, hardcore porn was easily accessible on video, the rich were getting greedier and richer, and divorce rates had peaked. With more women entering the workforce and an increasing number of newly-single kids were suddenly being left at home unsupervised. The public might have been content with leaving their kids at home, but a generation of ‘suddenly being left unsupervised for long periods of time’ were exposed to a plethora of violence and sex in media. Concern for the latchkey generation was only made worse by the abduction and murder of six-year-old Adam Walsh. The tragic case “created a nation of petrified kids and paranoid parents” who saw danger in every stranger they encountered. The media-fueled mass hysteria eventually led to a rash of Satanic panic.

It was enough to make any God-fearing White conservative clutch their pearls! Rather than blame Reagan for taking away childcare funding and completely botching the response to drugs and AIDS, or recognize that the risk strangers pose to children is minimal at best a vocal group of conservatives decided it was the loss of a nuclear family, declining morals, and demonic media that had left everything such a mess. Even if you didn’t buy into the whole “little Timmy will get murdered by Satanists because his mommy had to rejoin the workforce” school of thought, it was hard to deny the world was pretty scary, what with global warming, Jeffrey Dahmer, the cold war, and deadly invisible illnesses. Why couldn’t we go back to the way they were in the fifties when bad things only happened to minorities and women weren’t constantly going on about equal rights? Back before all teens were watching heavy metal videos on MTV, popping third generation birth control pills, and playing Super Mario Bros on their NES (or whatever they were into back then. Doing whippets maybe? I dunno, I was like 4 at the time). Cue a wave of 1950’s nostalgia and horror films that capitalized on the public’s fear for the safety of unsupervised kids.

Most slashers followed a basic formula. A group of unsupervised teenagers with poor decision making skills all did “Bad Things TM” until an evil man would show up and kill everyone but the clever, resourceful, virginal hero because they were too pure to be defeated by evil. The story was simple, yet effective — at least in its ability to terrify audiences. I doubt anyone waited for their wedding night because they were afraid Jason would show up for a murderous version of coïtus interruptus. Ironically the conservative adults whose fear and values inspired the horror Renaissance were also its main detractors. Probably because filmmakers were interested in making money, not PSAs about morality, and tits and blood sell. The so-called golden age of slashers began in 1978 with Halloween and ended in 1984 with A Nightmare on Elm Street. Unfortunately sequelitis and low budget direct-to-video horror flicks marked the end of the era, but thankfully schlock could be just as entertaining in all it’s goofy, cheesy glory. When 80’s horror is good, it’s really good, but when it’s bad it’s amazing. And it’s these B-movie slashers that make Cirque Berserk such a fun read. Guess understands that while The Shining may be the Michelin star-winning gourmet meal of eighties horror and the franchise slasher films are the family restaurants with mass appeal, movies like Basket Case and Slumber Party Massacre 2 are greasy fast-food burgers you cram in your maw at 3 A.M. in the CVS parking lot. Yes, they’re terrible for you, and yes you regret it the next day when you wake up with a hangover and smell like dumpster fries, but god damn if those weren’t some delicious fucking burgers. Cirque Berserk is what happens when you have a talented chef prepare those greasy, salty, fast-food burgers. It’s fast, fun, and you won’t be able to put it down until you’ve devoured the whole thing.

Guess cleverly subverts the standard slasher story line while still paying homage to many of its elements. There’s a cast of stereotypical teens whose bad judgement lands them in an abandoned amusement park with a masked killer despite the warnings from the wise old woman at the gas station. There’s stupid teen drama, bad puns, and buckets of blood. Guess even adds a Satanic subplot where a group of disenfranchised teens summon the demon Lilith to grant them wishes, poking fun at Yuppie parents’ unfounded fear that their kids were listening to Stairway to Heaven backwards and using D&D to summon demons. The story is full of self-aware humor, my favorite example of which involves one of the characters pointing out how weird it is that no one is carrying a gun in Florida. Curses and murderous Satan worshipers are well within the realm of possibility, but no one packing heat in a Southern “stand your ground” state is way too weird. Guess manages to give us all this and still make her story genuinely scary. And for what felt like a pretty standard slasher set-up, I was actually caught off guard by a plot twist.

When it comes to her villains, however, Guess dispenses with the usual “irredeemably evil for the heck of it” masked murderers typical in slashers. Instead, she gives us a group of tragic figures who sell their humanity for a chance at freedom. It’s appropriate that the teen killers summoned Lilith to grant them freedom, a figure who chose to become a demon rather than submit to the will of a man. As another famous Abrahamic rebel declares in Paradise Lost “Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.” The Alphabet of Ben Sira describes Lilith as Adam’s first wife, created as his equal. After getting fed up with her husband’s misogyny and bad sex, Liltith decides dick really isn’t worth all this bullshit and flies off into the night, choosing to become a demon rather than submit to male authority. Modern Jewish feminists, such as Judith Plaskow, interpret her as “a female symbol for autonomy, sexual choice, and control of one’s own destiny.” In her midrash, The Coming of Lilith, Plaskow writes “Lilith not only embodies people’s fears of how attraction to others can ruin their marriages, or of how risky childbearing and raising children are, but also represents a woman whom society cannot control—a woman who determines her own sexual partners, who is wild and unkempt, and who does not have the natural consequences of sexual activity, children.” Demon or no, Lilith sounds like my kind of woman.

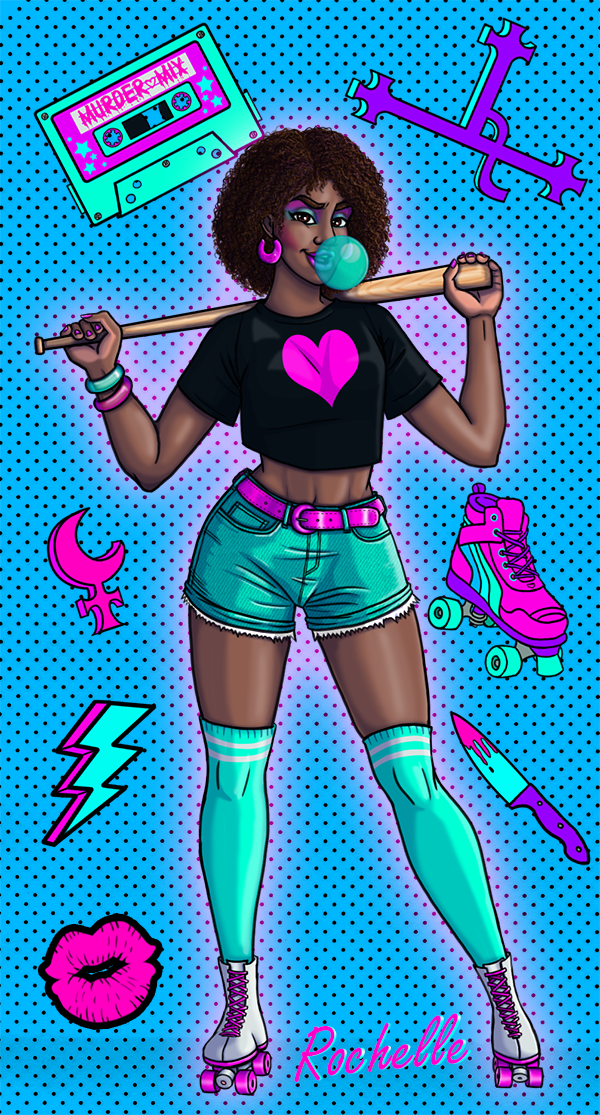

But my absolute favorite part of Cirque Berserk is Guess’ tough-as-nails and whip-smart protagonist, Rochelle, who is anything but your typical final girl. Guess got the name from Rachel True’s character in The Craft, whose frequent erasure from horror conventions and panel discussions Guess even wrote about here. She explains that this was her way of honoring True. “I love The Craft and I got the idea for Cirque Berserk a little after watching Horror Noir and hearing what Rachel said about being typecast as the best friend and always having to say “are you okay” a million different ways. My Rochelle is a response to that.” And I say she’s the perfect response! But what else would you expect from Guess, creator of the Black Girl’s Guide to Horror blog? Cirque Berserk is a novella for Black and Indigenous horror fans who are sick of getting cast as victims, and hero helpers. As Guess states on her website:

“Horror is for everyone, but it doesn’t always feel that way with the lack of representation in the genre. Final Girls? White. Heroes? White. Villains? White. Masters of Horror? Mostly all white. Even those who talk about horror are all for the most part White. [My site] is the answer to the too white, too male, too cis, too straight genre that so many of us love but don’t see much of ourselves in.”

The novella has very few problems. I felt like some of the descriptions were a bit lacking and Guess has a tendency to “tell” rather than “show.” The word choices could also get repetitive (for example using “said” repeatedly), but these are both fairly minor nitpicks for what’s otherwise a very strong story. I also wish we’d been given a little more time with the victims before they started getting picked off one by one, but I otherwise can’t complain about the novella’s pacing. Building suspense is a great way to make your story scary, but sometimes you want a horror book that gets straight to the killing spree instead of dicking you around for ten gore-free chapters. And Guess knows how to give the reader that instant blood-soaked satisfaction we crave. Her book was the perfect length: long enough to get its point across without letting the story drag. It may not be as fancy or polished as some award-winning, gourmet novel, but who gives a fuck? You know which one you’re going to be craving at 3 AM.