Formats: Print, audio, digital

Publisher: HarperCollins

Genre: Eldritch Horror, Mystery

Audience: Young Adult

Diversity: Puerto Rican main character and author, main character with anxiety disorder

Takes Place in: The Hamptons, NY

Content Warnings (Highlight to view): Ableism, Child Endangerment, Classism, Death, Forced Captivity, Mental Illness, Racism, Police Harassment

Blurb

All Gabi wants is to spend the summer in his room, surrounded by his Funkos and books, but with his mom traveling, his bags are packed for the last place he wants to visit—the Hamptons. Staying with his best friend should have him willing to peek out of his cave, but ever since Ruth’s nouveau riche family moved, their friendship has been off.

Surrounded by mansions, country clubs, and Ruth’s new boyfriend, Frost Thurston—the axis that Hampton society orbits around—it doesn’t take long for Gabi to feel completely out of place. But when he witnesses a woman being pulled under the ocean water, and no one—not the police or anyone else in the Hamptons—seems to care, Gabi starts to wonder if maybe the beachside town’s bad vibes are more real than he thought.

As the “accidental” deaths and drownings begin to climb, Gabi knows he’ll need proof to convince Ruth they’re all in danger. And while the Thurston family name keeps rising to the top, along with every fresh body, what’s worst is that all the signs point to something lurking beneath the water—something with tentacles and a thirst for blood. Can Gabi figure out how the two are intertwined and put an end to the string of deaths…before becoming the water’s next victim?

I received this product for free in return for providing an honest and unbiased review. I received no other compensation. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.

As an introvert, being forced out of my cave of books and horror movies and into new social situations is not my idea of a good time. Even more so if it means being surrounded by rich white people. I’ve seen Get Out, I know how that story ends. But that’s exactly how Gabriel (Gabi for short) is meant to spend his summer, with his white, Nouveau Riche best friend Ruth. Ruth has invited Gabi to her new house in the Hamptons to meet all her new, rich friends and basically make sure her bestie doesn’t spend the summer in his room glued to his computer. If you’re not familiar with the Hamptons, it’s a popular seaside resort with a large artist community where wealthy New Yorkers like to summer. But the Hamptons aren’t exclusively white (even if it sometimes seems that way). Sag Harbor was a refuge for upper and middle class Blacks starting in the 1940s and the Shinnecock Nation were the original inhabitants and still reside there today (which Cardinal makes a point of mentioning). And of course, there’s the Hampton’s Latin American population who make up the bulk of the workforce there.

Gabi adores Ruth (platonically): she’s feisty, independent, and extremely loyal to the people she loves. Unfortunately, who she loves right now is a guy name Frost who is the absolute worst. Gabriel has put up with Ruth’s bad taste in men for years, but Frost is definitely the bottom of the barrel:an arrogant hip-hop producer who’s used to getting his way. It’s interesting how Frost (not his actual name) profits off Black music while being white and owns a Basquiat (a Black, neo-expressionist street artist who rose to fame in the 1980s and sadly died of a heroin overdose at the age of 27), without sharing the artist’s anti-capitalist views or even really recognizing the themes of colonialism and class struggle in the artwork. It’s clear he only cares about Black culture as far as it makes him look cool. He also calls Ruth “Tiki” because her paternal great-grandmother was Native Hawaiian. Ew. But Ruth is Gabi’s best friend so he tries his best to get along with her new beau, no matter how loathsome he finds him. Okay, admittedly, he could try and be a little more accepting and less judgmental of everyone in the Hamptons, but Frost totally deserves it. The Hamptons aren’t completely terrible, though. Gabi gets to meet Lars, a pansexual restaurant owner who grew up in South Boston (yay Boston) and Georgina, a bartender and fellow horror fan with a dry sense of humor (and part of the aforementioned Latine workforce) who he strikes up a friendship with.

Irony of Negro Policeman by Jean-Michel Basquiat in 1981. Acrylic and oilstick on wood.

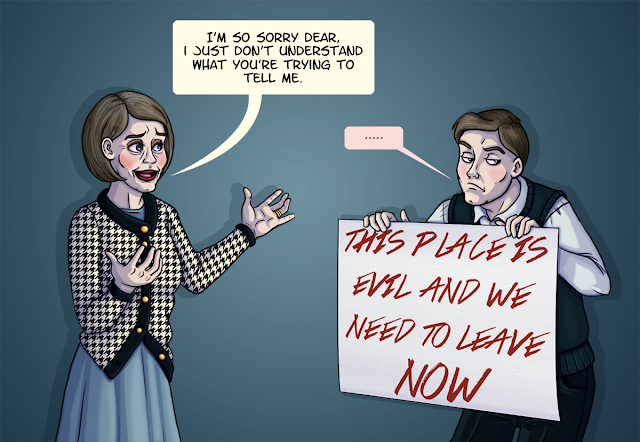

The class divide is clearly putting a strain on their friendship, with Gabi feeling afraid of getting replaced by Ruth’s new friends and left behind. Ruth is concerned by what she sees at Gabi’s lack off support and is also afraid of losing him. And it doesn’t help that Frost is whispering in her ear that Gabi’s jealous of her new life and trying to ruin it for him. It’s causing understandable tension and neither of them are entirely at fault for it. Gabi tends to deal with his insecurity by being snarky, even when people are trying to be nice to him, while Ruth keeps forcing Gabi into situations that make him uncomfortable and trying to get him to be friends with Frost. Clearly, both of them need to read up on Michael Suileabhain-Wilson’s Five Geek Social Fallacies, namely Geek Social Fallacy #4: Friendship Is Transitive (Ruth doesn’t seem to get that not all of her friends will get along, and that’s okay) and Geek Social Fallacy #3: Friendship Before All (Gabi needs to accept that Ruth is allowed to go off and live her own life without it being a slight on him).

While annoying at times, I think their behavior is not uncommon for young adults who are still learning the intricacies of relationships. As a grown up with a fully developed frontal lobe and years of experience with friendships, yes, the character’s behavior can be annoying. But for teenagers who have been friends since early childhood and are probably facing the idea of growing apart for the very first time, their actions make sense. Hell, I probably would have responded the same way at their age. And here is where I remind everyone this book is written for young adults, so if you’re older, you may not find the characters relatable. But that’s okay, the book isn’t for you. And honestly, I found both Gabi and Ruth well developed and likeable, even when they were acting like brats (again, they’re teenagers, it comes with the territory). I also really appreciated that there was no hint of romance between two friends. It’s nice to see them just be friends, as the “men and women can’t be friends” trope is one of my pet peeves.

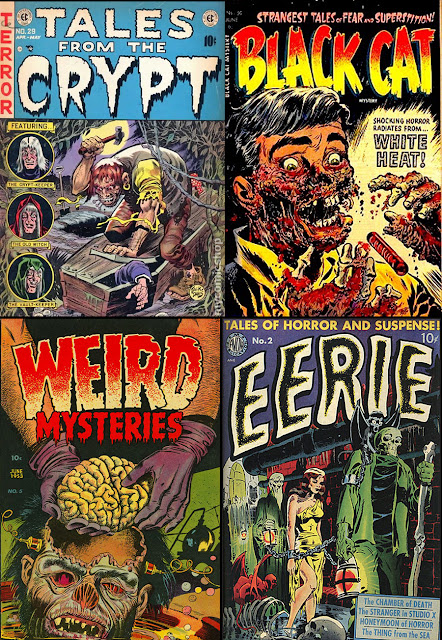

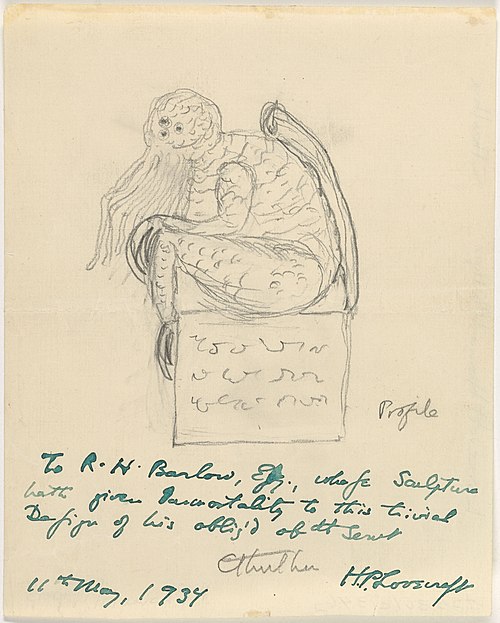

I’ve written before about how Lovecraft was a racist, sexist, xenophobic, antisemitic asshole to the point that even his wife and friends were calling him out on it. So, I love when marginalized authors use his works to create their own, progressive stories. The Horror at Red Hook is basically about how Black and Brown immigrants are a plague, so I love that Cardinal subverts this by making the white inhabitants the invaders instead (which historically they are) and gentrification the real plague on society. The wealthy colonizers are repeatedly compared to white poplars, an invasive tree species that was first introduced in the mid-18th century from Eurasia and that outcompetes many native North American species of plant.

There’s also a lot of talk of appropriation in the horror genre. Gabi’s online nemesis, @SonicReducer, points out that modern zombies are a whitewashed version of the original Haitian zombies who were a symbol of slavery. We learn from Georgina that Lovecraft stole his ideas of Cthulhu and the Great Old Ones from other cultures where the creatures actually existed, tying into the book’s themes of colonization. In reality Lovecraft was more likely inspired by Alfred Tennyson’s poem The Kraken and The Gods of Pegāna by Lord Dunsany. He despised anything that wasn’t Anglo-Saxon so I have a difficult time imagining he would have been willing to draw from cultures he viewed as “lesser” for his ideas. Still, fiction requires a willing suspension of disbelief and not me nitpicking a story about an eldritch horror terrorizing the Hamptons, so I’m willing to let it go for the sake of enjoying the story. Plus, it ties into the story’s themes of colonization.

A sketch of Cthulhu done by H.P. Lovecraft. Clearly Lovecraft was a better writer than he was an artist.

There is some ableism in the book, Gabi describes someone speaking to him as if he has a single digit IQ and refers to another character as looking like a “junkie” (a cruel name for people with substance use disorder), which I was not a fan of. Gabi also refers to Georgina’s make up as “punk rock war paint,” which made me side-eye. But overall, the book wasn’t especially problematic in any way.

I enjoyed the mystery elements, as I’m a total nerd when it comes to research and love when characters go to the library to discover the town’s dark past. In this case, Gabi and Georgina try to discover why people keep disappearing in the town, and if Frost’s family might be behind it. It’s pretty obvious who the bad guys are from the beginning so the mystery elements come more from how they’re making people disappear, why, and who’s next. There’s a sense of dread the hangs over the whole story that I found very effective. The pacing was decent, with enough horror elements to keep the book moving without sacrificing character development. Overall, You’ve Awoken Her is a good book for those looking for scares that aren’t too intense or gory. Body parts are found on the beach, but that’s about as gruesome as things get. While Gabi makes many references to horror films (both real and fictional) you don’t have to be a hardcore fan to enjoy the book.