Formats: Print, audio, digital

Publisher: Peachtree Teen

Genre: Blood & Guts, Body Horror, Ghosts/Haunting, Mystery, Gothic

Audience: Young Adult

Diversity: Neurodiversity (Autism), transgender characters, queer character

Takes Place in: LA, California

Content Warnings (Highlight to view): Abelism, Animal Death, Bullying, Child Abuse, Child Death, Child Endangerment, Death, Forced Captivity, Gaslighting, Gore, Homophobia, Kidnapping, Medical Torture/Abuse, Medical Procedures, Miscarriage, Oppression, Pedophilia, Physical Abuse, Rape/Sexual Assault, Self-Harm, Sexism, Slurs, Slut-Shaming, Torture, Transphobia, Verbal/Emotional Abuse, Victim Blaming, Violence

Blurb

Mors vincit omnia. Death conquers all.

London, 1883. The Veil between the living and dead has thinned. Violet-eyed mediums commune with spirits under the watchful eye of the Royal Speaker Society, and sixteen-year-old Silas Bell would rather rip out his violet eyes than become an obedient Speaker wife. According to Mother, he’ll be married by the end of the year. It doesn’t matter that he’s needed a decade of tutors to hide his autism; that he practices surgery on slaughtered pigs; that he is a boy, not the girl the world insists on seeing.

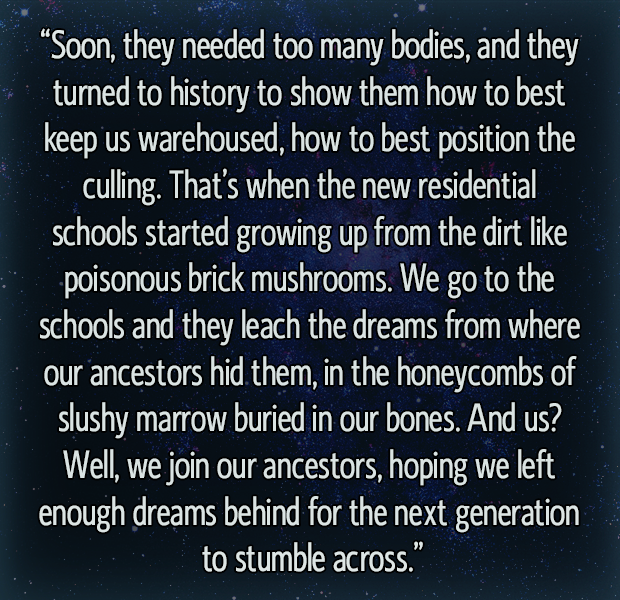

After a failed attempt to escape an arranged marriage, Silas is diagnosed with Veil sickness—a mysterious disease sending violet-eyed women into madness—and shipped away to Braxton’s Finishing School and Sanitorium. The facility is cold, the instructors merciless, and the students either bloom into eligible wives or disappear. When the ghosts of missing students start begging Silas for help, he decides to reach into Braxton’s innards and expose its guts to the world—if the school doesn’t break him first.

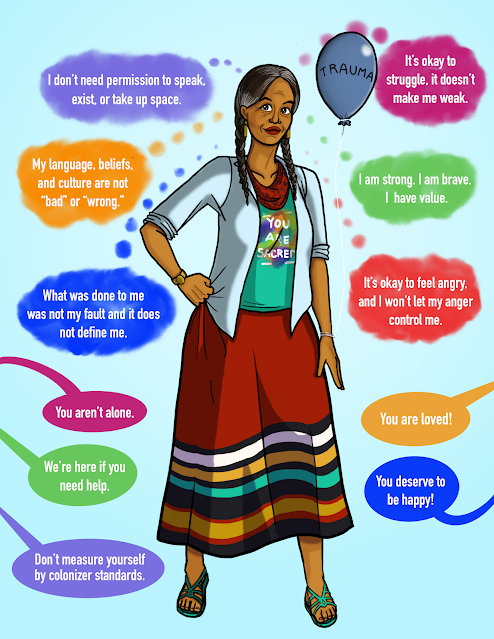

Featuring an autistic trans protagonist in a historical setting, Andrew Joseph White’s much-anticipated sophomore novel does not back down from exposing the violence of the patriarchy and the harm inflicted on trans youth who are forced into conformity.

I received this product for free in return for providing an honest and unbiased review. I received no other compensation. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.

Silas is an autistic trans boy living in Victorian London who wants nothing more than to be a surgeon like his brother, George, and his idol James Barry. Unfortunately for Silas, the world still sees him as a young girl with violet eyes.

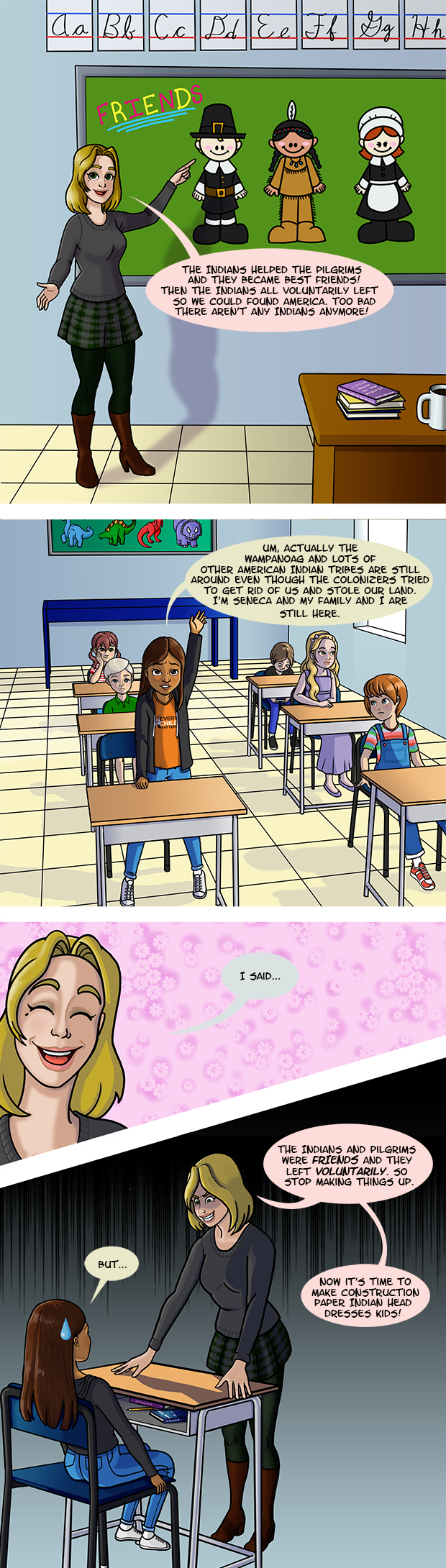

In White’s alternative history people born with violet eyes are Speakers, those who can open the Veil that separates the living and dead to communicate with ghosts. But only violet-eyed men are permitted to be mediums. It is believed that women who tamper with the Veil will become unstable and a threat to themselves and others. Veil sickness is said to be the result of violet-eyed women coming into contact with the Veil and is blamed for a wide range of symptoms from promiscuity to anger, but is really just the result of women who don’t obediently follow social norms. Thus, England has made it strictly illegal for women to engage in spirit work. After Silas’ failed attempt to run away and live as a man, he is diagnosed with Veil sickness and carted off to Braxton’s Finishing School and Sanitorium to be transformed into an obedient wife. Braxton’s is your typical gothic school filled with sad waifs and dangerous secrets, namely that girls keep disappearing. The headmaster is a creep and his methods for curing young girls are abusive. Despite the danger, Silas is determined to get to the bottom of the mysterious disappearances and find justice for the missing girls.

Violet-eyed women are highly valued as wives who can produce violet-eyed sons and are in high demand among the elite. Silas is no different, and his parents are eager to marry him off to any man with money. If being made to live as a girl weren’t bad enough, the idea of being forced to bear children is even more horrific to Silas. As someone who struggles with Tokophobia myself, I found White’s descriptions of forced pregnancy to be a terrifying and especially disturbing form of body horror. Because of Silas’ obsession with medicine, the entire book is filled with medical body horror. There are detailed descriptions of injuries and surgeries, medical torture, and an at-home c-section/abortion. Personally, I loved all the grossness and the detailed descriptions of anatomy and medical procedures. But The Spirit Bares its Teeth is most definitely not for the squeamish or easily grossed-out. I appreciated that in the afterword White made a point of mentioning that in the real world, it was usually racial minorities who were the subject of medical experimentation (rather than wealthy White women), and then recommended the books Medical Apartheid by Harriet A. Washington and Medical Bondage by Deirdre Cooper Owens for readers to learn more.

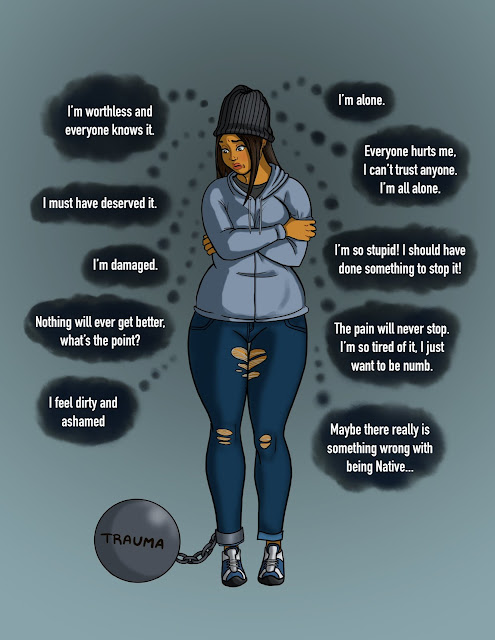

I was also happy to see an autistic character written by an autistic author. Stories about Autistic individuals often are told by neurotypical people who characterize autism as “tragic” or as an illness that needs to be cured. In The Spirit Bares its Teeth, neurodiversity is humanized and we see how harmful a lack of acceptance and understanding of autism is. Silas is forced to mask by society, and we see how difficult and harmful masking is to him. He is taught by his tutors to ignore his own needs in favor of acting the way others want. They reinforce the idea that acting “normal” (i.e. neurotypical) is the only way anyone will tolerate him. Silas’ tutors use methods similar to the highly controversial Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) to force him to behave in a manner they deem appropriate. He is not allowed to flap his hands, pace or cover his ears at loud noises, and is forced into uncomfortable clothing that hurts his skin and to eat food that makes him sick. He is mocked for taking things literally and punished if he can’t sit still and keep quiet. It’s horrible and heartbreaking.

Although I’m not autistic, I do have Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD), a condition which has many overlapping symptoms with autism, including being easily overstimulated by sensory input. I have texture issues and White’s description of the uncomfortable clothing Silas is forced into made my skin itch in sympathy. It sounded like pure hell, and poor Silas can’t even distract himself with stimming so he just has to sit there and endure it. After meeting a non-verbal indentured servant whose autistic traits are much more noticeable, he also acknowledges that his ability to mask gains him certain privileges as he can “pass” as neurotypical (even though he should never have to pass in the first place and doing so is extremely harmful to his wellbeing).

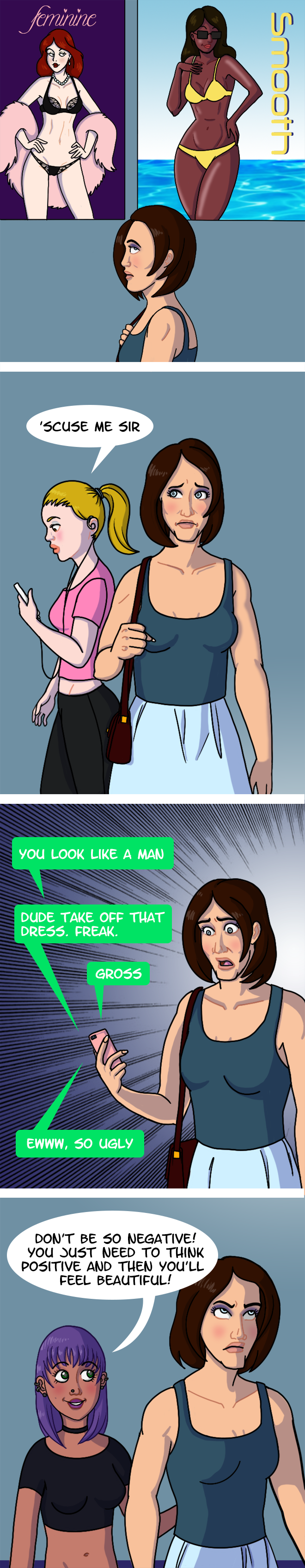

In addition to its positive autism representation, White also does an excellent job portraying the struggles of being a trans person forced to live as their assigned gender. Interestingly, this is the first book with a transgender main character I’ve read where said character isn’t fully out or living as their true gender. Part of the horror of the story is that Silas can’t transition as he’s in an unsupportive and abusive environment. I also found it interesting that Silas is both trans and autistic as there’s an overlap between autism and gender identity/diversity.

The Spirit Bares its Teeth is a suspenseful and deeply disturbing gothic horror story about misogyny, ableism, and how society tries and controls women. I was absolutely glued to this story and could not put it down, no easy feat when my ADD demands constant distraction. Each revelation was more horrifying than the last and by the end I was terrified of what secrets Silas would uncover next.