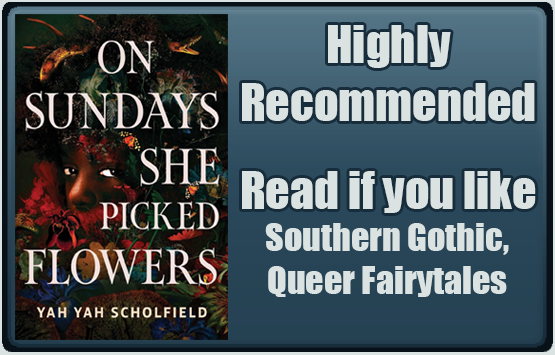

Formats: Print, digital

Publisher: Lanternfish Press

Genre: Gothic

Audience: Adult

Diversity: Author is Mackinac Bands of Chippewa and Ottawa Indian, main character is American Indian (unknown tribe), Gullah side characters

Takes Place in: South Carolina Sea Islands

Content Warnings (Highlight to view): Alcohol Abuse, Animal Death, Death, Drug Use/Abuse, Forced Captivity, Incest, Racism

Blurb

When Dr. Van Vierlans receives an invitation from Mrs. Elizabeth Van der Horst to give a lecture at her island mansion off the coast of South Carolina, he doesn’t think twice. There’s a generous honorarium, and he relishes the chance to revisit the Sea Islands, where he once studied the Gullah language.

The lavish house he arrives at is strangely out of time. No other historians appear, nor does an audience, as he passes the time chatting in Gullah with the household servants. Just when his suspicions become difficult to ignore, Mrs. Van der Horst plies him with a sumptuous feast that distracts him from her true motives–which may prove more sinister than anything he’s prepared to imagine.

I first read Van Alst’s work in the Indigenous dark fiction anthology, Never Whistle at Night. His story, The Longest Street in the World stood out to me because it was the first time I’d read an Indigenous story about an “Urban Indian.” The story took place in Chicago, home to the first Urban Indian center in the country, and author Theodore C. Van Alst Jr.

Van Alst’s main character in Pour One for the Devil, Dr. Van Vierlans, is also an urban Indian and an Ivy League trained junior professor of anthropology. Already I love this because we not only get to see an American Indian man with a PhD, but he’s also an anthropologist to boot. So often anthropologists are portrayed in media as white people studying “primitive” Indigenous people in remote areas, and the field itself is the product of colonialism, so it was refreshing to see an Indigenous anthropologist.

This Southern Gothic story begins with Dr. Van Vierlans being lured to the estate of the wealthy, white Elizabeth Morgenstern, with the promise of a generous honorarium for a lecture about the Coosaw shell rings. I was already getting vibes before the professor arrived, but then Auntie Delilah, a Gullah domestic worker at Morgenstern’s home, attempts to warn the doctor that both Elizabeth and the house are dangerous. Either due to ignorance (has he never seen a horror movie?!) or greed, Dr. Van Vierlans decides to ignore the warnings and stays anyway.

While taking a nap in one of the guest rooms Dr. Van Vierlans has a dream that the Devil is sitting on his chest. The Devil asks for a story about himself, and the doctor agrees to give him one, but in exchange Lucifer must leave him alone until Van Vierlans dies. The devil warns him that his death will be sooner than he expects, but even this isn’t enough to scare him away from Elizabeth’s House. It’s interesting that the devil appears to him at all,since Van Vierlans supports the traditional ways, unlike his father who insists on practicing Christianity.

At dinner the professor and his host engage in verbal combat. Dr. Van Vierlans finds Elizabeth Morgenstern, or Miss Lizzy, as she prefers to be called, fascinating. As a man from Chicago, he finds her rural Southern ways to be quaint. And because he’s an anthropologist, and familiar with the etiquette of different cultures, he’s able to impress Miss Lizzie with his impeccable manners. Elizabeth tells him about the automatons built by her late husband, Peter, which Delilah believes are powered by spirits.

I like how the American Indian man is portrayed as the cosmopolitan city mouse, while the country mouse is the wealthy white woman. He has studied her culture enough that he can easily blend in and impress the old white lady. Dr. Van Vierlans also becomes friendly with Auntie Delilah as he studied the Gullah as part of his work as an anthropologist and speaks Gullah creole (though Delilah points out he speaks it “like a little boy”).

I also really appreciated how Gullah is translated into a more formal style of English; a sociolect associated with the wealth and intelligence. Mitford popularized the idea of U (upper class) and non-U (non-upper class) English in the 1950s, which she claimed could determine what social class one belonged to. A person’s accent is also strongly associated with class. Because class is often erroneously tied to intelligence people will infer how smart someone is by what kind of English they speak. For example, standardized grammar often aligns with high IQ scores, and IQ tests have been show to favor people who are white and privileged. And no, it’s not because they’re smarter, IQ tests just aren’t accurate measures of intelligence. Gullah used to be (and sometimes still is) erroneously considered a mark of ignorance. By translating Gullah into “upper class English” (which Delilah and her sisters also speak fluently) Van Alst demonstrates that not only does the creole language have its own grammar and syntax rules, but that Gullah speakers are just as intelligent as those who speak a more formal English. The Gullah people are also described as “West Africa’s best and brightest farmers” who were enslaved and “forced to use their agricultural genius to grow rice crops on stolen land.” Again, Van Alst directly contradicts the racist stereotype that enslaved Black people were ignorant.

Auntie Delilah (whose true name is Nenge) was my favorite character. She is ethnically Mende (one of the largest ethnic groups in Sierra Leone), and her father and grandfather were Kamajor, respected hunters/warriors. She describes her childhood teachers as foolish white folks from up North who saw her and her people as souls to be saved. She learned about the bible and took her name from there as a middle finger to white Christians and the patriarchy. Delilah is happily unmarried and childfree, but is far from being a mammy stereotype. Instead, she’s chosen to remain single and without children because she enjoys her independence and doesn’t have the patience for a husband and child. I also always enjoy seeing happily childfree women in fiction.

I think some of the strongest aspect of Van Alst’s writing are his descriptions of nature and Elizabeth’s house. You could practically feel the humidity and smell the lush vegetation. I also enjoyed the humor, which balanced out the horror well. The ending was weird, not in a bad way, but it did leave me yearning for more of an explanation. It felt to me like the book ended abruptly before the story had finished, but I’m also not someone who enjoys vague endings.