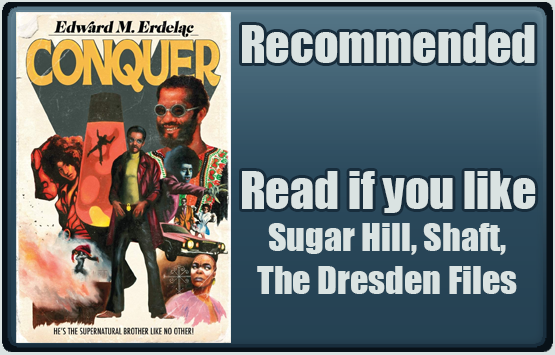

Formats: Print, audio, digital

Publisher: Self Published

Genre: Historic Horror, Monster, Mystery, Myth and Folklore, Occult, Vampire

Audience: Adult/Mature

Diversity: Black/African-American, Hispanic, Trans, Gay

Takes Place in: Harlem, New York, USA

Content Warnings (Highlight to view): Animal Death, Body Shaming, Child Abuse, Death, Drug Use/Abuse, Forced Captivity, Gore, Homophobia, Kidnapping, Necrophilia, Oppression, Pedophilia, Physical Abuse, Police Harassment, Racism, Rape/Sexual Assault, Sexual Abuse, Slurs, Transphobia

Blurb

In 1976 Harlem, JOHN CONQUER, P.I. is the cat you call when your hair stands up…the supernatural brother like no other. From the pages of Occult Detective Quarterly, he’s calm, he’s cool, and now he’s collected in CONQUER.

From Hoodoo doctors and Voodoo Queens,

The cat they call Conquer’s down on the scene!

With a dime on his shin and a pocket of tricks,

A gun in his coat and an eye for the chicks.

Uptown and Downton, Harlem to Brooklyn,

Wherever the brothers find trouble is brewin,’

If you’re swept with a broom, or your tracks have been crossed,

If your mojo is failin’ and all hope is lost,

Call the dude on St. Marks with the shelf fulla books,

‘Cause ain’t no haint or spirit, or evil-eye looks,

Conjured by devils, JAMF’s, or The Man,

Can stop the black magic Big John’s got on hand!

I received this product for free in return for providing an honest and unbiased review. I received no other compensation. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.

Conquer is the story of a Black mystical detective named John Conquer (a reference to John the Conqueror) and a homage to 70’s detective fiction and Blaxploitation films. It’s fun, well written, and full of creepiness, including a fetus monster haunting an abandoned subway station and a man shrunk down and boiled alive in a lava lamp. I greatly enjoyed the book, but like most Blaxploitation, it wasn’t without its problems.

It’s important to point out that Erdelac is a White author writing a Black story (something not uncommon in Blaxploitation). I usually prefer to promote “own voices” books, and stories by cishet White men are a rarity on this blog. After all, folks with privilege do not have the best track record when it comes to writing marginalized groups. As Irish author Kit de Waal said, “Don’t dip your pen in someone else’s blood”. Take American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins and The Help by Kathryn Stockett. They’re both terrible for numerous reasons including, but not limited to: not doing enough research, using the White Savior trope, watering down their narratives to make them palatable for White audiences, cultural appropriation, speaking over marginalized voices, etc. That’s not to say White authors shouldn’t write BIPOC characters at all. Not having any diversity in your story can be equally problematic. It just needs to be done carefully and respectfully. Very, very carefully. Yes, I know that can be a fine line to walk, but if an author can research what kind of crops people were growing in 1429 to make their book more accurate, they can research American Indians and people of color. Besides, that’s what hiring sensitivity readers and using resources like Writing with Color is for. Of course, there’s also the problem of White voices being given preferential treatment by publishers and audiences over BIPOC trying to tell their own stories.

To his credit, Erdelac has done an impressive amount of research to make his book feel authentic. John Conquer wears a dime around his ankle for protection and a mojo hand (another name for a mojo bag) for luck. His name is a reference to High John de Conqueror, a Black folk hero with magical abilities. Conquer also has one of the most accurate representations of Vodou I’ve ever seen in fiction. Hollywood “voo doo” is a pet peeve of mine, so I appreciate Erdelac’s dedication to portraying the religion and loa/lwa (the powerful spirits Vodou practitioners worship and serve) accurately. He also doesn’t try to portray an idealized version of 1970s NYC. There’s racism, anti-Semitism, homophobia, and cops and criminals spewing slurs. And while it’s jarring, it does make the story feel more authentic. The police are racist and homophobic and there’s tension between the many communities that make up 1970s New York. John Conquer’s Uncle Silas was disowned by his family for being gay, and when John is asked to solve his murder, he has to confront his own homophobia and transphobia. That doesn’t mean it always works, though. There were definitely a few times I side-eyed and wondered if a certain line really needed to be in there.

My favorite part of the book is Eldelac’s excellent world building. White vampires go up in smoke when exposed to sunlight, while vampires with more melanin are protected from the sun’s rays. Vampirism also halts a corpse’s decay, but all that rot catches up to them when they’re finally killed. Each culture has their own magical practices with distinct rules, and magic doesn’t cross cultural lines. For example, only Vodou practitioners can become zombies, and non-Christian vampires are immune to crosses. Conquer is especially powerful because he’s learned many different traditions and practices, but the catch is that this opens him to a wider variety of spiritual attacks. Street gangs utilize black magic to wage wars with each other. His work is clever, original, and something I could really get into. But…having White authors tell BIPOC stories still feels problematic to me when White authors are still so heavily favored by the publishing industry. I’ve reviewed books by White authors before, but because Conquer is based heavily on Blaxploitation it feels, well, more exploitative than those I’ve reviewed in the past. I’m still going to go ahead and recommend Eldelac’s work because—in the end—it is well written and interesting, but I can also completely understand if some of you want to skip this one.