Formats: Print, digital

Publisher: Ghoulish Books

Genre: Apocalypse/Disaster, Zombie

Audience: Adult/Mature

Diversity: Gay man author and main characters, main characters with AIDS

Content Warnings (Highlight to view): Animal Death, Child Death, Death, Drug Use/Abuse, Homophobia, Illness, Medical Procedure, Slurs, Suicide

Blurb

In The Only Safe Place Left is the Dark, an HIV positive gay man must leave the relative safety of his cabin in the woods to brave the zombie apocalypse and find the medication he needs to stay alive.

I received this product for free in return for providing an honest and unbiased review. I received no other compensation. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.

I was born during the beginning of the AIDS outbreak, during which my mom lost many of her gay friends. I remember the deep-rooted fear of AIDS that existed during my childhood. In grade school, we attended assemblies about the dangers of AIDS and how it was spread. There were public service ads about AIDS on every TV station. Parents wore red ribbons. As a queer teen I mourned the loss of an entire generation of gay and bisexual men.

One of the doctors I work with through my hospital, a gay man in his eighties who was one of the first physicians to treat AIDS patients, told me about the weekly funerals he attended. No one cared that gay men were dying of a mysterious illness during the conservative Regan administration. Little research was done on the epidemic. This doctor was one of the few who treated AIDS patients back then, using his knowledge of pharmacology to create a treatment regimen through off-label uses of already existing drugs. Of course, he couldn’t openly advertise his services due to the stigma in the medical community, so his patients found him through a whisper network and would visit him under the guise of getting a routine physical.

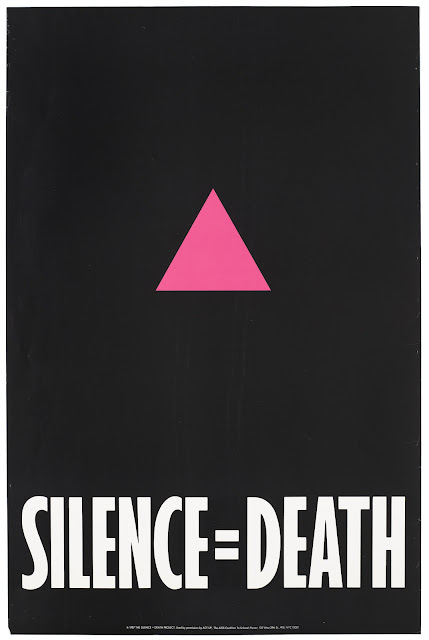

The Only Safe Place Left is the Dark is a unique zombie apocalypse novella about the AIDS epidemic. The cover of book is meant to invoke the iconic Silence=Death AIDS design from the late 1980s (a poster Quinton keeps in his Cabin). The title of the story comes from a quote in the play The Destiny of Me by writer and activist Larry Kramer, who is best known for co-founding the grassroots political group the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). In the first chapter of the book, Wagner references a New York Times article from July 3, 1981 entitled Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals. The article discusses an outbreak of Kaposi’s Sarcoma in New York and San Francisco, a form of cancer that can form lesions on the skin and in the mouth. It wasn’t yet known, but this sub-type of KS was caused by the immune suppression from some of the first HIV cases in the country.

Wagner’s zombie virus (if it even is a virus) is particularly terrifying because its victims, referred to as “The Afflicted,” are still awake and aware of what’s happening to them and powerless to stop it. They can feel themselves rotting and falling apart, even being eaten by flies. The zombies don’t want to hurt anyone but are completely unable to control their hunger, so they’ll scream warnings to their victims and plead for forgiveness as they tear them apart. Most disturbingly, they’ll beg uninfected humans to kill them. I suspect the Wagner’s zombies are loosely based on AIDS victims, as zombies are often an allegory for infectious disease. In her journal article Attack of the Living Dead Virus: The Metaphor of Contagious Disease in Zombie Movies English professor Cecilia Petretto explains that, “Much of our fear lies within the nature of disease itself… Disease, ugly as death, has its association with evil stemming back to the Black Plague.” What was known about AIDS was largely based on misconception, and AIDS victims were shunned and regarded as dangerous, much like the Hollywood zombies. In 1986, an article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association about AIDS was entitled Night of the Living Dead II: Slow Virus Encephalopathies and AIDS. Dr. Arthur Fournier, who encountered his first AIDS patient in 1979 while working with Miami’s Haitian community, compared the virus to “the zombie curse.” Before the advent of active antiretroviral therapy (ART), an AIDS diagnosis was often a death sentence. In that way AIDS patients were like the living dead, dying but not truly dead as their bodies were slowly destroyed and they wasted away. Wagner even describes them as “Waiting for a cure. Waiting for the end. They weren’t dead yet, but they weren’t alive either. They were zombies.”

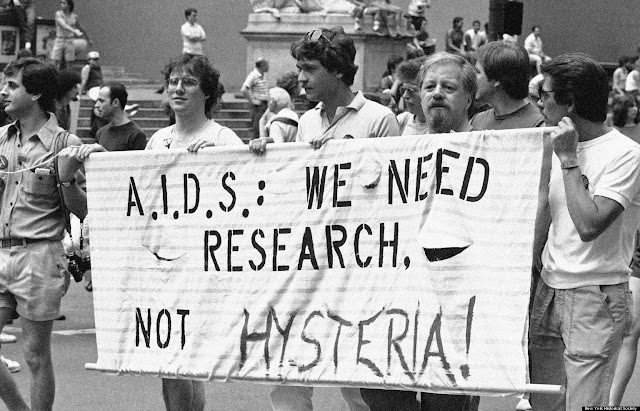

A group advocating AIDS research marches down Fifth Avenue during the 14th annual Lesbian and Gay Pride parade in New York, June 27, 1983. This year’s parade is dedicated to victims of the incurable disease AIDS which primarily afflicts homosexual men. (AP Photo/Mario Suriani)

Kept alive for 26 years by his antiretroviral medication, Quinton is one of the few humans who survived the zombie apocalypse–survived being the operative word, as he’s not really living, just surviving. He’s all but given up on love and compassion or anything ever getting better. His love for his deceased boyfriend, Frankie, brought him so much pain he’s now become a gruff loner. It’s safe to say Quinton may also be suffering from survivor’s guilt, as both he and his boyfriend were HIV positive but he survived while Frankie died. Worse, Frankie died when Quinton wasn’t there. The story switches between Quinton’s memories of Frankie’s last days and the present.

While out scavenging for more antiretroviral, Quinton meets Billy, a fellow gay man who’s managed to survive the apocalypse and is also HIV positive. But while Quinton has become cold, Billy still openly cares for others, which Quinton sees as a liability. Billy also believes in working together and the importance of community, while Quinton prefers to avoid other people. We learn that one of the reasons Billy has stayed alive so long is because those who are HIV positive are immune to the zombie virus. I thought this was an interesting twist, as outside of The Last of Us, Cooties, and Blood Quantum I’ve never seen a human with a natural immunity to Zombies in media. AIDS ravages the immune system, yet for some reason protects Quinton and Billy from turning into Afflicted. Being the kind of person who reads science articles about theoretical zombie biology, I did want to know how it all worked, but honestly an explanation isn’t important to the narrative.

I had a few nitpicks when it came to Billy, a Black character. While he was written well, “Black” was not capitalized when describing him. When referring to race, Black should always be capitalized. Billy was also described as having dreadlocks. As far as I know Billy was not a Rastafarian, therefore his hairstyle should be referred to as locs, not dreadlocks. While these examples are relatively minor issues, it does highlight the importance of doing your research and using sensitivity readers when writing about groups different than your own.

Wagner’s writing is very spartan; there are no grandiloquent descriptions or deep introspections. Instead, he gets his point across without the need for flowery adjectives or metaphors. The only part where this proved an issue for me was when it came to Quinton and Billy’s relationship, which felt very rushed. Otherwise, I appreciated Wagner’s straight-to-the-point style. It’s not often we get a new take on Zombies, but Wagner’s Afflicted managed to add a whole new level of horror to the undead. The history of AIDS is seamlessly interwoven, never forced, throughout the narrative. Wagner uses horror fiction to not only educate readers in a way that feels natural and respectful, but to capture the feelings of despair no doubt felt by many during the AIDS epidemic. The message is clear. Having AIDS may feel bleak, and every day is a fight for survival, but even amongst all the horror there is always love and hope.