Formats: Print, digital

Publisher: Independently Published

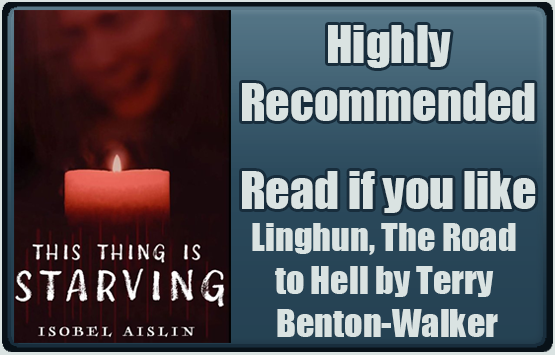

Genre: Ghosts/Haunting, Historic Horror

Audience: Adult/Mature

Diversity: Asexual main character, trans man character, lesbian character

Takes Place in: Pennsylvania

Content Warnings (Highlight to view): Alcohol Abuse, Child Abuse, Child Death, Death, Drug Use/Abuse, Forced Captivity, Gaslighting, Homophobia, Medical Procedure, Mental Illness, Pedophilia, Rape/Sexual Assault, Self-Harm, Sexism, Slurs, Slut-Shaming, Suicide, Transphobia, Victim Blaming, Violence

Blurb

It’s just a house, right? Houses can’t hurt. Houses can’t bleed.

But this house wants you to.

When the Waite family moves into their new home, they don’t bargain on being unwanted guests. But this house has deep-rooted, blood soaked history, and it’s angry. This Thing is Starving is an unflinchingly feminist love letter to the abused, bursting with feminine rage and told from the perspective of a haunted house.

Warning, this review discusses abuse, rape, and the sexual abuse of minors.

The house on 4377 N. Oscar St is haunted. But this is not your typical haunted house story. This story is told from the house’s point of view as it witnesses the tragedies that befall its owners throughout the year. The house is haunted by four women and one trans boy. The first, and oldest, is Lillian. She lived in the house with her husband in the 1920s and is the most unstable of the five ghosts. Jason was a teenaged, closeted trans boy from the 1950s. Lila was a lesbian from 1975 who hated her queerness. In 2002 the house was owned by a woman named Karissa, a child abuse survivor who struggles with low self-esteem. The final ghost is Kay, a teenaged girl who died in the house after it was abandoned by Karissa in the early 2000s. All the ghosts are victims of abuse, sexual assault, or other forms of violence at the hands of men, and they all met with tragic ends either by their own hand or at the hands of others.

Veronica Waite and her family are the house’s most recent inhabitants. Her mother, Louise, moved them there after escaping an abusive partner and is doing her best to start over. The house immediately takes a disliking to the family, with its wild and grubby children and Louise who it immediately labels a “bad mother” due to her love of wine, parentification of Veronica, and inability to keep track of all her children. The only exception to the house’s ire is Veronica, whom the house feels strangely drawn to. It views her as “a splotch of brightness amongst the gloom” and tries its best to communicate with the eldest Waite child. Veronica certainly seems happy in the beginning. She finds a new friend quickly, makes the cheerleading team, and even lands a hot, football playing boyfriend. She creates beautiful art to hang in her attic room. But then things start to unravel for the family, and the house can do little to stop it. As Veronica struggles with her asexuality and trying to take care of her siblings, she slowly learns how cruel the world can be to women and girls.

Most of the men in this story are horrible, even an old man whose obituary Louise is editing. I’m sure the “not all men” crowd will object to the fact that almost all the cisgender men (and boys) in the story are awful human beings (admittedly sometimes to the point of feeling like caricatures), but I believe this is intentional. The story is being told from the point of view of the house, and the house hates men. Because the house can only witness what happens within its walls, or the lives of the unhappy ghosts who haunt it, the house rarely gets to see the good parts of humanity. Statistically, the majority or murders and rapes are committed by men, so of course the ghosts are more likely to be victims of male violence, leading to the house believing that all men are inherently bad. Toward the end of the book, a character named Owen shows up who is devoid of the toxic traits shown by most of the other male characters. While he clearly has a crush on his female coworker, he respects her boundaries, supports her decisions, and keeps his desire to protect her in check. But of course, the house can’t recognize that he’s a good man like the audience can, and immediately hates Owen.

Ironically, the house is reinforcing harmful gender stereotypes because it doesn’t understand the complexities and nuances of abuse. It can only see people as innocent victims (women, girls, and AFAB people) or evil perpetrators (cisgender men and boys). But characterizing men as inherently evil gives them permission to behave horribly, as it rejects the notion that they have control over their actions. Essentially, it’s a more insidious form of “boys will be boys.” But men can, and need to, do better. The house also conveniently ignores the fact that women can not only support the harmful actions of men, but can be perpetrators themselves, and that men can be victims, but Aislin does not. Lillian is abused by her serial killer husband, but when she finally snaps and kills him, she doesn’t free the women he has chained in the basement. Instead, she replaces her husband as the predator in the house and kills them. She even slut shames her husband’s victims, justifying their rapes and murders to herself. Veronica’s younger twin brothers, Charlie and Sawyer, are also revealed to be victims of their father’s abuse (especially Sawyer). Sadly, like Lillian, Sawyer becomes an abuser himself, acting out what he experienced at the hands of his father on his little sister Leslie. The house makes an exception for Jason, a trans man, another victim of male violence, but not for the twins. I suspect that’s because the house is mildly transphobic, and sees Jason as a woman, even though he’s clearly a man and his ghost has a male-presenting form.

While the house feels a fierce protectiveness of Veronica and her baby sister, it shows a cold indifference to their brothers. Interestingly, Louise was also abused by her husband, yet the house doesn’t group her in with other victims. Instead, it views her with scorn for “failing” to protect her girls (but not the boys). This is another sign that the house is not entirely free from its own sexist bias and doesn’t fully understand how abuse works. The house’s hatred of Louise is understandable, with its strong desire to protect, it cannot comprehend a mother “failing” to do so. The problem is that the house expects her to be perfect just because she’s a mom, even though Louise is a victim herself and doing the best she can under the circumstances. She loves her children, and tries her best to protect them, even when the police fail to.

Sadly, judging mothers who are being abused is not an uncommon occurrence. In an interview with NPR, Mother Jones reporter Samantha Michaels explains “It’s basically sexism. Most of the legal experts that I talked with said that it comes down to a cultural expectation that women are responsible for what happens in the home. There’s an expectation that they should be the moral center of the family, that they should reign in the man’s worst impulses, and that they should do whatever they can to protect their child, even if it means, you know, sacrificing themselves.” Mothers can have their children taken from them, and are even sent to prison due to Draconian “failure to protect” laws. Kerry King is one such mother, who is serving a 30-year sentence in prison for not protecting her daughter from their abuser, John Purdy, who is only serving 18 years for abusing King and her daughter. On October 26, 2004 in the case of Nicholson v. Williams the New York Court of Appeals ruled that children who witnessed abuse were wrongfully removed from their mother’s care, and that their non-abusive mothers had not been “neglectful” simply because they were unable to protect their children from witnessing domestic abuse.

This Thing is Starving starts with statistics about the rape, exploitation, and abuse of women and girls. Aislin states that the story is dedicated to the women who never get justice and whose stories are never heard. The book reminds me of rape revenge films without the sensationalism/exploitation common for the genre, similar to Promising Young Woman and Revenge (both films notably have female directors). Except, in this story, most of the victims don’t get revenge. Revenge against an abuser may be satisfying in fiction, but it rarely happens in real life where men often get away with hurting women. This makes the book feel more realistic. And when the house, full of pain and rage, lashes out and tries to hurt abusers and rapists, it usually hurts the innocent as well.

For example, when the house violently kills the teen boys who attempt to rape Kay, she also gets caught in the crossfire and is killed. Hate and anger rarely hurt just the intended target, but others as well. As Maddie Oatman so eloquently puts in her rape revenge article for Mother Jones “These stories offer a retributive vision of justice, the violence of the man mirrored back onto him. Traditional gender roles are flipped—the woman is the predator, and the man is the prey—but the basic shape of the conventional revenge story is unchanged. Witnessing women take revenge in film and fiction may offer a cathartic thrill, but the trope can also function as a trap; vengeance replicates the same power structure the avenger wishes to hold accountable.” She further goes on to explain “But justice can and should mean something other than the balancing of harms, as prison and police abolitionists and other activists have argued. In resisting the carceral approach to punishment, they advocate a politics of structural change, of experimentation and openness to new social forms. These ideas demand a radical artistic approach to match, a breaking free of the traps of the revenge plot. A couple of recent works give us a sense of this. Call it the reparative mode.”

Aislin shows us that there are other, healthier ways to heal from trauma than hunting down and killing your rapist (something victims are sadly arrested for in real life). And honestly, I really appreciate that Aislin presents more realistic ways that survivors can heal from trauma, like leaning on others they trust for support and opening up about what happened. Instead of perpetuating the cycle of violence like the house does, the survivors heal by breaking free of it. This Thing is Starving is certainly a difficult and heart-wrenching read that contains abortion, rape, revenge porn, conversion therapy, drug addiction, suicidal thoughts, an infant’s death, pedophilia, trauma, a minor doing sex work, and transphobia. But Aislin doesan amazing job handling the difficult topics of abuse, sexual assault, and trauma without making the story feel like trauma porn.

0 Comments